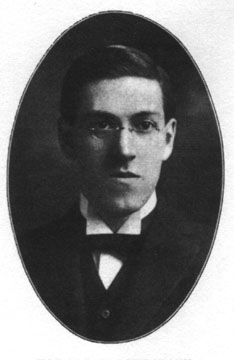

As for myself and the conditions under which I write

- I'm afraid that's a rather unimportant subject, since in plain fact I

am a very mediocre and uninteresting individual despite my queer tastes,

and have hardly produced anything worth calling real literature. However

- here are a few data.

I am a prosaic middle-aged creature about to turn 39 on

the 20th of next month - a native of Providence, of old Rhode Island stock

on my mother's side and more closely English on my father's side. I was

born on what was then the Eastern Edge of the settled district, so that

I could look westward to paved streets and eastward to green fields and

woods and valleys. Having a country-squire heredity, I looked east oftener

than west; so that to this day I am three-quarters a rustic.

At the present moment I am seated on a wooded bluff above

the shining river which my earliest gaze knew and loved. This part of my

boyhood world is unchanged because it is a part of the local park system

- may the gods be thanked for keeping inviolate the scenes of which my

infant imagination peopled with fauns and satyrs and dryads!

My taste for weird things began very early, for I have

always had a riotously uncontrolled imagination. I was afraid of the dark

until my grandfather cured me by making me walk through vacant rooms and

corridors at night, and I had a tendency to weave fancies around everything

I saw. Very early, too, began my taste for old things which is so

strong a part of my present personality.

Providence is an ancient and picturesque town, built originally

upon a precipitously steep hillside up which still wind the narrow lanes

of colonial times with their carved, fanlighted doorways, iron-railed double

flights of steps, and tapering Georgian steeples. This dizzy, ancient precipice

lies on the route between residence and business sections, and from infantile

glimpses of it I acquired a fascinated reverence for the past - the age

of periwigs and three-cornered hats and leather-bound books with long s's.

My taste for the latter was augmented by the fact that

there were many in the family library - most of them in a black windowless

attic room to which I was half-afraid to go alone, yet whose terror-breeding

potentialities really increased for me the charm of the archaic volumes

I found and read there.

Weird stuff always captivated me more than anything else

- from the very first. Of all the tales told to us in infancy the fairy

lore and witch and ghost legends made the deepest impressions. I began

to read fairly young - at four - and Grimm's Fairy Tales formed my first

continuous reading. At five I read the Arabian Nights, and was utterly

enthralled. I made my mother fix up an Arabian corner in my room - with

appropriate hangings, lamps, and objects d'art purchased at our local "Damascus

Bazaar" - and I assumed the fictitious appellation of Abdul Alhazred;

a name I have ever since whimsically cherished, and which I have latterly

used to designate the author of the mythical Al Azif or Necronomicon.

At about six I tuned to Graeco Roman mythology, lead gradually

by Hawthorne's "Wonder Book" and "Tanglewood Tales", and by a stray copy

of "The Odyssey" legend in Harper's Half-Hour Series. At once I dismantled

my Baghdad corner and became a Roman - turning to Bulfinch's "Age of Fable"

and haunting the museums of classical art here and in Boston. It was around

this time that I first began my crude attempts at literature. I was literate

on paper - with printed characters - as soon as I could read; but did not

attempt any original composition till around my sixth birthday, when I

painfully acquired the art of writing in script. Curiously, the first stuff

I wrote was verse; since I had always had an ear for rhythm, and

had very early got hold of an old book on "Composition, Rhetorick, and

Poetic Numbers" printed in 1797 and used by my great-great grandfather

at the East Greenwich Academy about 1805.

The first of these infantile verses I can remember is

"The Adventures of Ulysses"; or, "The New Odyssey", written when I was

seven. This began: "The night was dark, O reader hark! and see Ulysses'

fleet all homeward bound, with vict'ry crown'd, he hopes his spouse to

greet. Long he hath fought, put Troy to naught, and levell'd down. But

Neptune's wrath obstructs his path, and into snares he falls."

Mythology was my life-blood then, and I really almost

believed

in the Greek and Roman deities - fancying I could glimpse fauns and satyrs

and dryads at twilight in those oaken groves where I am sitting now. When

I was about 7 years old, my mythological fancy made me wish to be - not

merely to see - a faun or a satyr. I used to try to imagine that

the tops of my ears were beginning to get pointed, and that a trace of

incipient horns was beginning to appear on my forehead - and bitterly lamented

the fact that my feet were rather slow in turning into hooves! Of all young

heathen, I was the most unregenerate. Sunday school - to which I was sent

when five - made no impression on me; (though I loved the old Georgian

grace of my mother's hereditary church, the stately First Baptist, built

in 1775) and I shocked everybody with my pagan utterances - at first calling

myself a Mohammedan and then a Roman pagan. I actually built woodland alters

to Pan, Jove, Minerva, and Apollo, and sacrificed small objects amidst

the odour of incense. When, a little later, I was forced by scientific

reasoning to discard my childish paganism, I was to become an absolute

atheist and materialist. I have since given much attention to philosophy,

and find no valid reason for any belief in any form of the so-called spiritual

or supernatural.

The cosmos is, in all probability, an eternal mass of

shifting and mutually interacting force-patterns which our present visible

universe, our tiny earth, and our puny race of organic beings, form merely

a momentary and negligible incident. Thus my serious conception of reality

is dynamically opposite to the fantastic position I take as an aesthete.

In aesthetics, nothing interests me so much as the idea of strange suspensions

of natural law - weird glimpses of terrifyingly elder worlds and abnormal

dimensions, and faint scratchings from unknown outside abysses on the rim

of the unknown cosmos. I think this kind of thing fascinates me all the

more because I don't believe a word of it!

Well - I began to write weird tales at the age of 7½

or 8, when I had my first glimpse of my idol Poe. The stuff was very bad,

and most of it is destroyed; but I still have two laughable specimens done

when I was 8 - "The Secret of the Grave" and "The Mysterious Ship". I didn't

write any really passable tales till I was 14. When between 8 and 9, my

whole tastes took an abrupt turn, and I became wild over the sciences -

especially chemistry. I had a laboratory fitted up in the cellar, and spent

all my allowance for instruments and textbooks. In these whims I was much

indulged by my mother and grandfather (my father having died), since I

was very sickly - almost a nervous invalid.

When 7 I took up the violin, but abandoned it in boredom

2 years later and have never since had a good musical taste. I could not

attend school much, but was taught at home by my mother and aunts and grandfather,

and later by a tutor. I had brief snatches of school now and then, and

managed to attend high school for four years - though the application gave

me such a nervous breakdown that I could not attend the university. As

a matter of fact, I never had any decent heath until eight or nine years

ago - though now, oddly enough, I seem to be developing into quite a lean,

tough old bird!

My youthful science period proved of long duration; though

I carried on literary attempts at the same time, also played much like

any youngster. I was not interested in games and sports, and am not now

- but liked forms of play which included the element of dramatic impersonation;

war, police, outlaw, railway, etc. From chemistry I gradually shifted to

geography and finally to astronomy, which was destined to enthrall

me and influence my thought more than anything else I ever encountered.

I obtained a small telescope, - which I have still - and began writing

voluminously on the heavens. I still have some of my old mss., and a hectographed

copy of my juvenile periodical "The Rhode Island Journal of Astronomy".

At the same time my curious antiquarianism began to get more and more emphatic.

Living in an ancient town amidst ancient books, I followed

Addison, Hope, and Dr. Johnson as my models in prose and verse; and literally

lived in their periwigged world, ignoring the world of the present. When

I was 14 my grandfather died; and in the financial chaos ensuing, my birthplace

had to be sold. This dual deprivation gave me a tinge of melancholy which

had hard work wearing off; for I have very strong geographical attachments,

and worshiped every inch of the rambling house and park-like grounds and

quaint foundations and shadowy stable where my youth had been spent. It

was long my hope to buy back the home "when I became rich" - but before

many years I saw that I utterly lack the acquisitive instincts and ability

needful for monetary success.

Commercialism and I can't get on speaking terms, and since

that gloomy year of 1904 my history has been one of increasing constriction

and retrenchment.

Till the death of my mother we had a flat near the old

home. Then came ill-starred excursions into the world, including two years

in New York, which I learned to hate like poison. Now I have a room in

a quiet Victorian backwater on the crest of Providence's ancient hill,

- in a sedate old neighborhood that looks precisely like the residence

section of a sleepy village.

My elder aunt - in frail health and unable to keep house

- has a room in the same dwelling; and since both she and I retain as much

as possible of the old family furniture, pictures, and books (the rooms

are very large) there is still much of the old home atmosphere hereabouts.

Knowing I shall never be rich, I shall be very contented

if I can hang on here the rest of my days - in a quiet place much like

my early scenes, and within walking distance of the woods, fields, and

river-banks where I roamed in childhood. My principle remunerative occupation

is the professional revision of prose and verse for other writers - a hateful

task; but more dependable than the hazards of original writing when one

does not produce popular and easily saleable work.

I do my own tales whenever I get the chance, which isn't

as often as I'd like. Whenever possible, I take my writing out in the open

in a black leatherette case - sometimes to my beloved wooded river-bank,

and sometimes to the wilder countryside north of Providence. My one purely

recreational hobby is antiquarian travel - visiting other ancient towns

and studying examples of Colonial architecture. My lean purse makes my

excursions sadly limited, but even so I have arranged to cover quite a

little historic ground from Vermont to Virginia during the last few years.

The first stuff I ever had printed was a regular monthly

series of astronomical articles in a local daily. I was sixteen when these

began, and I surely felt important. Meanwhile I was beginning to doubt

my fictional ability, and was turning to verse. At 18 I decided I couldn't

write stories, and burned all my tales save a few grotesque infant experiments

and two of my later things - "The

Beast in the Cave" and "The

Alchemist". I am not sorry for this, for the stuff really was detestably

immature. What does make me feel ridiculous is the serious way I took my

verse-writing at this period - for in cold truth I never was or will be

a real poet!

My illusions persisted because at that time I was a semi-invalid

and much of a recluse, so that I did not receive a wide array of salutary

criticism. Then - at age 24 - I joined an amateur literary society whose

activities were conducted by correspondence; and thereby secured some highly

valuable encouragement and critical suggestions. I wish that organization

were as vigorous today as then - but unfortunately it has become moribund

beyond all ordinary powers of resuscitation. My ambitions, which had dropped

from science to literature when it became clear that my health would not

permit of the arduous application of astronomical or chemical research,

now became further clarified; and I was made to see little by little that

prose and not verse was my rightful medium. At the same time the most conspicuous

18th century eccentricities began to drop away from my style.

In 1916 I let one of the amateur editors in my literary

group print one of the two tales which I had saved from the holocaust of

1908; and was immediately thereafter told by a friend that weird fiction

was my one and only real forte - the one and only point at which I had

any chance of making an actual contact with genuine artistic achievement.

I was half incredulous at first, for I had distrusted

the worth of my tales; but upon persuasion decided to try again after my

9-year fictional silence. The results were "The

Tomb" and "Dagon",

written respectively in June and July of 1917. I half-feared that my rustiness

in story-telling would make these new attempts worthless, but was soon

assured that they greatly surpassed the 2 surviving tales of my youth.

Then I started in earnest, producing a vast number of

new stories of which I have saved about 7/8. I had no idea of a steady

professional market till "Weird Tales" was founded - and I still doubt

if any other periodical would stand regularly for my stuff.

It doesn't look so bad beside the unutterable junk forming

the bulk of "W.T.'s" contents, but I fear it wouldn't stand very high considered

as literature - beside such real literature as the work of Poe, Machen,

Blackwood, James, Bierce, Dunsany, de la Mare, and so on. The highest honor

I've so far received is a three-star mention and bibliographical note in

O'Brien's "Best Short Stories of 1928" - based on my "Colour

Out of Space".

Well - that's about all there is to me! Not much, but

you see how garrulous a vain old man becomes when someone gives him provocation

for talking about himself!

That's the kind of guy I am - a cynic and materialist

with classical and traditional tastes; fond of the past and its relics

and ways, and convinced that the only pursuit worthy of a man of sense

in a purposeless cosmos is the pursuit of tasteful and intelligent pleasure

as promoted by a vivid mental and imaginative life. Because I believe in

no absolute values, I accept the aesthetic values of the past as the only

available points of reference - the only workable relative values - in

a universe otherwise bewildering and unsatisfying.

Thus I am an ultra-conservative socially, artistically,

and politically, though an extreme modernist despite my 39 years in all

matters of pure science and philosophy. Loving the illusory freedom of

myth and dream, I am devoted to the literature of my escape; but likewise

loving the tangible anchorage of the past, I tincture all my thought with

overtones of antiquarianism.

My favorite modern period is the 18th century; my favorite

ancient period, the virile world of unspoiled republican Rome. I can't

get interested in the middle Ages - even the magic and legendry of that

dreary era seems to me too naive to be really convincing.

Turning to my love of getting out of the real world into

an imaginary world, I tend to prefer night to day when not in the open

country. Accordingly my hours are fearful and wonderful at home - usually

up at sunset and to bed in the morning.

I am seldom out late - but seldom up early! In winter

I virtually hibernate, for I am abnormally sensitive to the cold. Even

a little coolness knocks me silly! on the contrary, I don't know what it

is to be hot. I begin to tighten up at 95 in the shade!

All told I am pretty much of a hermit, as I was in youth.

Most of my literary associates - a congenial "gang" some of whose names

you'll recognize from W.T. tables of contents (Frank Belknap Long Jr.,

Donald Wandrei, Clark Ashton Smith, H. Warner Munn, Wilfred B. Talman,

August W. Derleth, etc., etc.,) - live in other localities, and I'm getting

too old to enjoy conversation on other than my favorite topics.

Old age claimed me early. Temperamentally I about the

same as I was 20 years ago, as I'll be 20 years hence if I'm alive then.

As for writing - I usually know what I want to say before I start a tale,

but often change the plot midway if the actually penning suggests some

new idea. I do all work in long hand - I can't even think with a cursed

machine in front of me - and correct very minutely.

The extreme rapidity with which I write matter not destined

for publication gives place to a very slow-moving caution when I table

a piece of seriously intended prose. I apply great attention to details,

including rhythm and tone-colour; though my aim is for the greatest possible

simplicity - the art which conceals art. I usually spend about three days

on a tale of medium length - in sessions of varying duration. I don't like

to break the train of thought, so don't let any other task interrupt.

I never write except when the inward demand for expression

becomes insistent. Nothing excites my contempt so much as forced or mechanical

or commercial writing. Unless one has something to say, he had better keep

quiet! I have a commonplace-book in which I jot down weird notions and

plot germs for later use, and also have a file of weird newspaper cuttings

as a possible source of ideas and colour-touches. A few tales I have founded

on actual dreams - my own being very weird and fantastic. In youth I had

more nightmares than I do now - when at six I used to encounter quite regularly

a frightful species of dream-demons which I named "night-gaunts". I've

used them in one

of my tales. I do my best writing between 2 A.M. and dawn.

What I dread most is typing my Mss., for I abhor the sight

and sound of a machine. I can't get anyone else to do it for me, since

nobody can read my Mss. in their scrawled, interlined, and repeatedly corrected

state. Sometimes I can't decipher them myself!

Now I guess there isn't much more to be said about either

the would-be author or his effusions!

Finally, I must apologise for this present flood of senile

garrulity! This is the way old age gets when given occasion to recall bygone

days - especially when the environment is unchangedly suggestive of the

past as is this wooded river-bluff.

But the west is blazing red with a departed sun, and above

the ancient treetops the thin silver sickle of a young moon is troubling.

I must get home...