Lovecraft was always proud

to say he was influenced by the great writers of the eighteenth and

nineteenth century. He was less likely to admit it but the lesser writers

of his youth had an equal or greater influence. One of these was Robert

W. Chambers, a painter turned author who published his greatest work

of horror when Lovecraft was only five. But it was reprinted numerous

times within his life and HPL spoke of it fondly. In a way, Chambers

betrayed Lovecraft by giving up horror and becoming on of the most successful

writers of popular fictions of the first two decades of the twentieth

century.

Though fame in his lifetime came

from his succession of best-selling "shop-girl" society romances and

historical novels, Robert William Chambers (1865-1933) is perhaps

best remembered today for his horror and fantasy stories. In his day,

his historical and romance novels earned him the title "the Shopgirl

Scheherazade" and "the barker of the New York society side show."

H. L. Menken called him "the Boudoir Balzac." But even within his

lifetime the audience for such books fell away with the new literature

of the twenties and thirties and the coming of the second world war.

Robert William Chambers was born

in Brooklyn on May 26, 1865, to William P. Chambers (1827 -

1911), a famous lawyer, and Caroline Chambers (née Boughton),

a direct descendant of Roger Williams, the founder of Rhode Island.

It was a family of wealth and social standing and the children were

expected to excel. Robert's brother was Walter Boughton Chambers,

the world famous architect.

Chambers

was educated at the Brooklyn Polytechnic Institute. There, and at

his grandfather's estate in the Adirondacks, he discovered in his

love of nature and outdoor sportsmanship a talent for drawing.

Chambers

was educated at the Brooklyn Polytechnic Institute. There, and at

his grandfather's estate in the Adirondacks, he discovered in his

love of nature and outdoor sportsmanship a talent for drawing.

At twenty, he studied painting

at the Art Students' League in New York where he became friends with

another student, Charles Dana Gibson, later to gain fame as a magazine

and book illustrator. There is a legend that the young Chambers

and Gibson took sketches to the editor of Life, then a humor

magazine, looking for their first job. The editor accepted Chambers's

work and turned down Gibson so scornfully that Gibson resolved never

to submit a drawing again.

At 21, in 1886, he went to Paris

for seven years to study at the École des Beaux Arts and, later,

the Julien Academy. He studied under Cormon, Lefebvre, Boulanger,

Collin, and Doucet. He first exhibited in the Paris salon in 1889.  He

returned to New York in 1893 and began selling illustrations to Life,

Truth, Vogue, and other magazines.

He

returned to New York in 1893 and began selling illustrations to Life,

Truth, Vogue, and other magazines.

Chambers published his first

book, In the Quarter (1894), a melodrmatic tale of student

life in Paris published as an anonymous volume. He had originally

written it in Munich in 1887. It appeared in an anonymous edition.

One critic said "it might yield a libretto for another 'La Bohême.'"

Its success was enough to inspire a second work and it was the second

literary work that really took off and changed the young man's life.

It even encouraged his publisher to re-release In the Quarter

with the author's name and reference to the second work.

In 1895, Chambers published a

remarkable collection of ten eerie short stories, The King in

Yellow. It appeared during a period when a lot of people unlikely

to writer horror stories did so. Perhaps inspired by success of Ambrose

Bierce, the rise of spiritualism, or the impending turn of a century

which often creates emotional and spritual uncertainty, architect

Ralph Adams Cram wrote his collection of ghost stories entitled Black

Spirits and White (1895), historical novelist F. Marion Crawford

wrote "The Upper Berth" (1894), humorist W. W. Jacobs wrote

the horrific story "The Monkey's Paw," Henry James wrote The

Turn of the Screw, and children's book author Mrs. Nesbit

wrote Grim Tales (1893).

The

King in Yellow is the most striking of all collected horror

story works in that the title refers to a fictional play which becomes

in integral part of a number of stories which are otherwise unrelated.

The play "The King in Yellow"

to which the title refers is said to drive those who read it

insane. The first four stories, "The Repairer

of Reputations," "The Mask," "In the Court of the Dragon,"

and "The Yellow Sign," concern people who have come across

copies of the rare and banned play. Horrific tragedy strikes all who

remain sane after reading it. The middle two tales are a classic ghost

story and a poetic, mystical trifle. The last four tales harken back

to Chambers's first novel, revolving around the Paris student art

scene but all involve some small, eerie twist.

The

King in Yellow is the most striking of all collected horror

story works in that the title refers to a fictional play which becomes

in integral part of a number of stories which are otherwise unrelated.

The play "The King in Yellow"

to which the title refers is said to drive those who read it

insane. The first four stories, "The Repairer

of Reputations," "The Mask," "In the Court of the Dragon,"

and "The Yellow Sign," concern people who have come across

copies of the rare and banned play. Horrific tragedy strikes all who

remain sane after reading it. The middle two tales are a classic ghost

story and a poetic, mystical trifle. The last four tales harken back

to Chambers's first novel, revolving around the Paris student art

scene but all involve some small, eerie twist.

In his treatise The Supernatural

in Literature Lovecraft wrote of Chambers's work: "Very genuine,

though not without the typical mannered extravagance of the eighteen-nineties,

is the strain of horror in the early work of Robert W. Chambers, since

renowned for products of a very different quality. The King

in Yellow, a series of vaguely connected short stories having

as a background a monstrous and suppressed book whose perusal brings

fright, madness and spectral tragedy, really achieves notable heights

of cosmic fear in spite of uneven interest and a somewhat trivial

and affected cultivation of the Gallic studio atmosphere made popular

by Du Maurier's Trilby."

And the collection has been recognized

for its value. The King in Yellow has often been repeatedly

reprinted and anthologized to the present day.

This this success, Chambers dropped

his artistic career and turned to writing. The Woman's Movement

and the typewriter were changing the social structure of America as

young women entered the workplace, sought respectability in business,

and earned there own disposable income. A great deal of this

income would go toward the purchase of Chambers novels. Chambers

spoke to the romantic and social needs of these women. For the

next few years he alternated between fantastic fiction - The

Maker of Moons (1896), The Mystery of Choice

(1897) - and historical novels - The Red Republic, 1894;

Lorraine, 1896; Ashes of Empire, 1897.

This series of four romances centered around the Franco-Prussian War

(including The Maids of Paradise, 1903) was began

at the same time he was writing The King in Yellow.

As with his later historical novels, these all have young American

as their heroes. In Ashes of Empire a group of dashing

young Americans assist the Empress Eugénia to escape, hat and

all, from Paris.

After

the Franco-Prussian novels, he tackled the American Revolution

with his most famous novel, Cardigan, 1901 followed

by The Maid-at-Arms, 1902; The Hidden Children,

1914; The Little Red Foot, 1921.

After

the Franco-Prussian novels, he tackled the American Revolution

with his most famous novel, Cardigan, 1901 followed

by The Maid-at-Arms, 1902; The Hidden Children,

1914; The Little Red Foot, 1921.

In reaching this young audience

Chambers helped create the image of young Americans in the new century.

The working woman was for a short time called "the Chambers Girl."

This was quickly supplanted by Chambers's friend Charles Dana Gibson,

who illustrated the majority of the Chambers society novels, used

his own merchandising skills to promote "the Gibson Girl." It

was often said that while Gibson helped create a visual look for the

newly emerging, turn-of-the-century working woman, Chambers, in his

society novels, gave her a voice.

On July 12, 1898, Chambers married Elsa Vaughn Moller

(1882 - 1939). They had a son, Robert Edward Stuart Chambers

(later calling himself Robert Husted Chambers) who also gained some

fame as an author.[1] At a New York office, whose address was

unknown even to his family, Robert W. Chambers wrote from ten to six.

The family split their time between New York and a luxurious house

in Broadalbin, New York at the foot of the Adirondack Mountains.

Fishing and hunting were his relaxations. The novelist was a well

set-up man, with square shoulders and chin and a gray mustache. His

manner was cordial and genial. Robert and Elsie were active

members of New York society as can be seen by Elsie's 1910 gift to

the Metropolitan Museum of Art of The Old Mill (Vieux Moulin) [ca.

1892] by American impressionist Theodore Robinson (1852-1896)

[1] Note. Robert Husted Chambers: The change to "Husted" may

have come from one of his father's novels: the 1902 novel The

Maids-at-Arms was dedicated to Miss Katharine Husted.

As a young boy around 1912 Lena Dalkeith dedicated her book "Stories

from Roman History" to him and a Robert Husted Chambers short story

Captain Sebastien appeared in the December 1922.

[1] Note. Robert Husted Chambers: The change to "Husted" may

have come from one of his father's novels: the 1902 novel The

Maids-at-Arms was dedicated to Miss Katharine Husted.

As a young boy around 1912 Lena Dalkeith dedicated her book "Stories

from Roman History" to him and a Robert Husted Chambers short story

Captain Sebastien appeared in the December 1922.

A New York socialite himself,

in 1906 Chambers turned to contemporary society with six novels beginning

with The Fighting Chance (1906) and concluding with

The Streets of Ascalon (1912) and including four others.

These took on topical subjects like love and the class and monetary

obstacles of marriage, the dangers of alcohol, and the guestion of

divorce. In these novels, usually illustrated by Charles Dana Gibson,

Chambers showed the weakness he, and Gibson, had in understanding

the emergence of the independent woman. This did not stop women from

flocking to read his novels but a later critic could remark that "despite

the vogue for the Chambers heroine at the time, she was markedly less

convincing than his men."

Throughout his career, Chambers

would often return to horror, often mixing it delightfully with mystery

and action in the vein of Sax Rohmer. Some of the best include In

Search of the Unknown (1904) and The Slayer of Souls

(1920).

In his first twenty years as a popular writer, Robert

W. Chambers produced forty-five volumes, “veering in accordance with

the breeze of popular demand.” According to some estimates, Chambers

was one of the most successful literary careers of his period, his

later novels selling well and a handful achieving best-seller status.

Many of his works were also serialized in magazines.

The period of 1915-1919 had its quota of war novels.

In 1924 he returned to historical fiction, with the

same easy fluency but small critical acclaim, although magazines continued

to pay high prices for his serials.

A critic said of his historical

novels that they, "exhibited his ability to handle crowds, invent

exciting incident, and exercise his painter's dexterity in painting

vivid landscapes." A typical example of his descriptive powers can

be found in a passage from "The White Shadow" (The Mystery

of Choice):

Then the daily repeated

miracle of the coming of dawn was wrought before our eyes. The heavens

glowed in rainbow tints; the shredded mist rising along the river

was touched with purple and gold, and acres of meadow and pasture

dripped precious stones. Shreds of the fading night-mist drifted among

the tree tops, now tipped with fire, while in the forest depths faint

sparkles came from some lost ray of morning light falling on wet leaves.

Then of a sudden upshot the sun, and against it, black and gigantic,

a peasant towered, leaning upon his spade.

And Chambers knew how to write for

his audience. "I write the sort of stories," says Chambers, quoted in

Authors Today and Yesterday, "which at the moment it amuses me to write;

I trust to luck that it may also amuse the public." And they liked it.

He was a top selling author of genre novels, often on the best seller

list, and increasingly wealthy from his craft. An enclopedia of

the time said, that "despite his years, Mr. Chambers already ranks among

the foremost writers of romantic fiction. His style has been compared

to Anthony Hope, but although both these brilliant writers deal with

the same class of subjects and characters Mr. Chambers discovers an

individuality and originality which sufficiently differentiate him from

any others of his school."

"I have always liked to change,

to experiment--just as I used to like to change my medium in painting,

aquarelle, oil, charcoal, wast, etc," he said and proved it by alternating

between novels, short stories, poems, magazine articles of natural

history, military subjects, and hunting and fishing, and novels. For

the actress Ada Rehan he wrote a play, The Witch of Ellangowan,

it is said, in one weeks' time. It was produced at Daly's Theatre

in New York city during the spring of 1897. His musical comedy Iole,

made from his novel of that title, was produced in New York in 1913.

His historical novels, already covering the Franco-Prussian War and

the American Revolution, went on to include a series on World War

One, the War of 1812, The Civil War, and the French and Indian Wars.

He even wrote a novel about Captain Kidd, The Man they Hanged.

His 1906 novel The Tracer of Lost Persons provided the

basis for the long-running radio series "Mr. Keen, Tracer of Lost

Persons" from which many television series took inspiration.

But like many popular novelists,

Chambers became increasingly a man of leisure, pounding out his novels

to pay for his real pleasures. In town he was a popular club man,

a member of the National Institute of Arts and Letters and belonged

to a wide number of clubs: the Century Club (like his father before

him), the Metropolitan Club, the Authors' Club (New York), Triple

Island, Broadalbin Game, Union, Saratoga Golf, Rockwood Hall, and

the Calumet Club of New York among others.

Authors Today and Yesterday

says: "During the winter months Chambers lives in New York City and

has an office, the location of which not even his family knows. Here

he writes daily from ten to six, secure from distraction. He says

his stories have the most erratic way of developing. 'Sometimes I

begin with the last chapter, sometimes in the middle, and sometimes

I lay out an elaborate skeleton. The despair of my publisher is this

uncertainty of working method. I have sometimes written thirty thousand

words, waited two weeks to decide what should happen next, and torn

up the whole thirty thousand to get rid of the dilemma. It was much

easier for me to do that than to doctor the manuscript.'"

His work in town was a seasonal

affair. Every summer, Chambers and his family would retreat to the

family estate in Broadalbin, New York, in the foothills of the Adirondacks.

The house, built early in the nineteenth century by his grandfather,

Dr. William Chambers, was rebuilt for him by his brother, Walter Boughton

Chambers, the architect.  Chambers

and his wife filled the house with Chinese and Japanese antiques,

medieval armor, and rare rugs. On the eight hundred acres Chambers

could pursue his love of nature, hunting with his dog, fishing, collecting

butterflies, and riding horses. He was, rare for his time, an ecologist,

an avid planter of trees (20,000 it is said).

Chambers

and his wife filled the house with Chinese and Japanese antiques,

medieval armor, and rare rugs. On the eight hundred acres Chambers

could pursue his love of nature, hunting with his dog, fishing, collecting

butterflies, and riding horses. He was, rare for his time, an ecologist,

an avid planter of trees (20,000 it is said).

After 1924, Chambers devoted

himself exclusively to historical subject. Though a good deal of his

audience had deserted him, he continued to write with the same "easy

fluency but to small critical acclaim, although magazines continued

to pay high prices for his serials." Chambers died in New York City

on December 16, 1933 following abdominal surgery.

Chambers had 14 of his works turned into movies in

his lifetime. One of his books, The Common Law, was filmed three times.

Chambers has always traveled with the rich and powerful, we see that

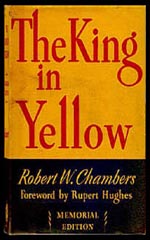

in his books.  That

he knew Rupert Hughes, the uncle of Howard Hughes, is a fact. Rupert

Hughes wrote the 1933 introduction to the memorial re-issue of The

King in Yellow.

That

he knew Rupert Hughes, the uncle of Howard Hughes, is a fact. Rupert

Hughes wrote the 1933 introduction to the memorial re-issue of The

King in Yellow.

Ultimately, after his death his critics looked down

on his body of work. H.P. Lovecraft said of him in a letter

to Clark Ashton Smith, "Chambers is like Rupert Hughes and a few other

fallen Titans - equipped with the right brains and education but wholly

out of the habit of using them." Frederic Taber Cooper commented,

"So much of Chambers's work exasperates, because we feel that he might

so easily have made it better." As a writer he exhibited his

ability to handle crowds, invent exciting incident, and exercise his

painter’s dexterity in painting vivid landscapes.

It

is an interesting contrast between Chambers and Lovecraft. While Lovecraft

thought highly of Chambers's early horror stories and abhorred the

later work as selling out, Robert W. Chambers is almost exactly the

writer Lovecraft dreamed of being: the Gentleman Writer. Lovecraft

repeatedly spoke of his desire to be able to live comfortably, write

as he pleased while living off the profits of that writing, and pursuing

the gentlemanly pleasures of sport, scienific knowledge, and collecting.

He aspired to be a Lord Dunsany. Though Chambers did not have a title,

he had more in common with Dunsany than Lovecraft in everything but

dedication of horror and fantasy.

It

is an interesting contrast between Chambers and Lovecraft. While Lovecraft

thought highly of Chambers's early horror stories and abhorred the

later work as selling out, Robert W. Chambers is almost exactly the

writer Lovecraft dreamed of being: the Gentleman Writer. Lovecraft

repeatedly spoke of his desire to be able to live comfortably, write

as he pleased while living off the profits of that writing, and pursuing

the gentlemanly pleasures of sport, scienific knowledge, and collecting.

He aspired to be a Lord Dunsany. Though Chambers did not have a title,

he had more in common with Dunsany than Lovecraft in everything but

dedication of horror and fantasy.

But Lovecraft also hated dogs,

sloppy writing, and romantic plot lines. Chambers loved hunting dogs,

a beautiful and often half-naked woman in his plot lines, and didn't

seem to mind a bit if the critics thought he was too flowery in his

description (often excellent but extended). It is a tragedy that his

lurid and gory serialized story The Slayer of Souls

was printed in book form without removing the repetitive updating

of plot line every few chapters. But he lived a full and happy life.

That seemed to be what he was after. And he has left the world with

a dozen or more brilliant novels and tales out of his vast production

of over seventy works. For who is there who can write passages describing

fear and desolation as well today as Chambers in "The Repairer

of Reputations":

"This

is the thing that troubles me, for I cannot forget Carcosa where black

stars hang in the heavens; where the shadows of men's thoughts lengthen

in the afternoon, where the twin suns sink into the Lake of Hali;

and my mind will bear forever the memory of the Pallid Mask. I pray

God will curse the writer, as the writer has cursed the world with

this beautiful, stupendous creation, terrible in its simplicity, irresistible

in its truth a world which now trembles before the King in Yellow."