IN

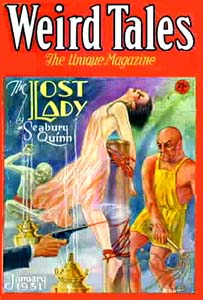

ONE sense, it is a mere truism to speak of the evocative power of words.

The olden efficacy of subtly woven spells, of magic formulas and incantations,

has long become a literary metaphor; though the terrible reality which

once underlay and may still underlie such concepts has been forgotten.

However, the necromancy of language is more than a metaphor to Sir Roderick

IN

ONE sense, it is a mere truism to speak of the evocative power of words.

The olden efficacy of subtly woven spells, of magic formulas and incantations,

has long become a literary metaphor; though the terrible reality which

once underlay and may still underlie such concepts has been forgotten.

However, the necromancy of language is more than a metaphor to Sir Roderick

Hagdon: the scars of fire on his ankles are things which no one

could possibly regard as having their origin in a figure of speech.

Sir Roderick Hagdon came to his title and his estate with no definite

expectation of inheriting them, nor any first-hand knowledge of the sort

of life and surroundings entailed by his inheritance. He had been born

in Australia; and though he had known that his father was the younger brother

of Sir John Hagdon, he had formed only the vaguest idea of the ancestral

manor; and the interest that he felt therein was even vaguer. His surprize

was little short of consternation when the deaths of his father, of Sir

John Hagdon and Sir John's only son, all occurring within less than a year,

left clear his own succession and brought a letter from the family lawyers

informing him of this fact—which otherwise might have escaped his attention.

His mother, too, was dead; and he was unmarried; so, leaving the Australian

sheep-range in charge of a competent overseer, he had sailed immediately

for England to assume his hereditary privileges.

It was a strange experience for him; and, strangest of all, in view

of the fact that he had never before visited England, was the inexplicable

feeling of familiarity aroused by his first sight of the Hagdon manor.

He seemed to know the farm-lands, the cottages of the tenants, the wood

of ancient oaks with their burdens of Druidic mistletoe, and the old manor-house

half hidden among gigantic yews, as if he had seen them all in some period

that was past recollection. Being of an analytic trend, he attributed all

this to that imperfect sitmultaneousness in the action of the brain-hemispheres

by which psychologists account for such phenomena. But the feeling remained

and grew upon him; and he yielded more and more to its half-sinister charm,

as he explored his property and delved in the family archives. He felt

also an unexpected kinship with his ancestors—a feeling which had lain

wholly dormant during his Australian youth. Their portraits, peering upon

him from the never-dissipated shadows of the long hall wherein they hung,

were like well-known faces.

The manor-house, it was said, had been built in the reign of Henry

the Seventh. It was mossed and lichened with antiquity; and there was a

hint of beginning dilapidation in the time-worn stone of the walls. The

formal garden had gone a little wild from neglect; the trimmed hedges and

trees had taken on fantastic sprawling shapes; and evil, poisonous weeds

had invaded the flower-beds. There were statues of cracked marble and verdigris-eaten

bronze amid the shrubbery; there were fountains that had long ceased to

flow; and dials on which the foliage-intercepted sun no longer fell. About

it all there hung an air of shadow-laden time and subtle decadence. But

though he had never known anything but the primitive Australian environment,

Hagdon found himself quite at home in this atmosphere of Old World complexities—an

atmosphere that was made from the dissolving phantoms of a thousand years,

from the breathings of dead men and women, from loves and hates that had

gone down to dust. Contrary to his anticipations, he felt no nostalgia

whatever for the remote land of his birth and upbringing.

Sir Roderick came to love the sunless gardens and the overtowering

yews. But, above and beyond these, he was fascinated by the manor-house

itself, by the hall of ancestral portraits and the dark, dusty library

in which he found an amazing medley of rare tomes and manuscripts. There

were many first editions of Elizabethan poets and dramatists; and mingled

with these in a quaint disorder, were antique books on astrology and conjuration,

on demonism and magic. Sir Rodereck shivered a little, he knew not why,

as he turned the leaves of some of these latter, volumes, from whose ancient

vellum and parchment arose to his nostrils an odor that was like the mustiness

of tombs. He dosed them hastily; and the first editions were unable to

detain him; but he lingered long over certain genealogies and manuscript

records of the Hagdon family filled with a strange eagerness to learn as

much as he could concerning these shadowy forbears of his.

In going through the records, he was struck by the brevity of the

mention accorded to a former Sir Roderick Hagdon, who had lived in the

early Seventeenth Century. All other members of the direct line had been

dealt with at some length; their deeds, their marriages, and their various

claims to distinction (often in the role of soldiers or scholars) were

usually set forth with a well-nigh vainglorious unction. But concerning

Sir Roderick, nothing more was given than the bare dates of his birth and

death, and the fact that he was the father of one Sir Ralph Hagdon. No

mention whatever was made of his wife.

Though there was no obvious reason for more than a passing surmise,

the present Sir Roderick wondered and speculated much over these singular

and perhaps sinister omissions. His curiosity increased when he found that

there was no portrait of Sir Roderick in the gallery, and none of his mysterious

unnamed lady. There was not even a vacant place between the pictures of

Sir Roderick's father and son, to indicate that there ever had been a portrait.

The new baronet determined to solve the mystery, if possible: an element

of vague but imperative disquietude was now mingled with his curiosity.

He could not have analyzed his feelings; but the life and fate of this

unknown ancestor seemed to take on for him a special significance, a concern

that was incomprehensibly personal and intimate.

At times he felt that his obsession with this problem was utterly

ridiculous and uncalled-for. Nevertheless, he ransacked the manor-house

in the hope of finding some hidden record; and he questioned the servants,

the tenants and the people of the parish to learn if there were any legendry

concerning his namesake. The manor-house yielded nothing more to his search;

and his inquiries met with blank faces and avowals of ignorance: no one

seemed to have heard of this elusive Seventeenth Century baronet.

At last, from the family butler, James Wharton, an octogenarian who

had served three generations of Hagdons, Sir Roderick obtained the clue

which he sought. Wharton, who was now on the brink of senility, and had

grown forgetful and taciturn, was seemingly ignorant as the rest; but one

day, after repeated questioning, he remembered that he had been told in

his youth of a secret closet behind one of the book-shelves; in which certain

manuscripts and heirlooms had been locked away several hundred years before;

and which, for some unknown reason, no Hagdon had ever opened since that

time. Here, he suggested, something might be found that would serve to

illumine the dark gap in the family history. There was a cunning, sardonic

gleam in his rheumy eyes as he came forth with this tardy piece of information,

and Sir Roderick wondered if the old man were not possessed of more genealogical

lore than he was willing to admit. All at once, he conceived the disquieting

idea that perhaps he was on the verge of some abominable discovery, on

the threshold of things that had been forgotten because they were too dreadful

for remembrance.

However, he did not hesitate: he was conscious of a veritable compulsion

to learn whatever could be learned. The bookcase indicated built the half-senile

butler was one which contained most of the volumes of demonism and magic.

It was now removed; and Sir Roderick went over the uncovered wall inch

by inch. After much futile fumbling, he located mod pressed a hidden spring,

and the door of the sealed room swung Open.

It was little more than a cupboard, though a man could have concealed

himself within it in time of need. Doubtless it had been built primarily

for some such purpose. From out its narrow gloom the moldiness of dead

ages rushed upon Sir Roderick, together with the ghosts of queer exotic

perfumes such as might have poured from the burning of unholy censers in

Satanic rites. It was an effluence of mystery and of evil, Within, there

were several ponderous brazen-bound volumes of mediaeval date, a thin manuscript

of yellowing parchment, and two portraits whose faces had been turned to

the wall, as if it were unlawful for even the darkness of the sealed door

to behold them. Sir Roderick brought the volumes, the manuscript and the

portraits Forth to the light. The pictures, which he examined first, represented

a pan and woman who were both in the bloom of life. Both were attired in

Seventeenth Century costumes; and the new Sir Roderick did not doubt for

a moment that they were the mysterious couple concerning whom the family

records were so reticent.

He thrilled with a strange excitement, with a feeling of some momentous

revelation that he could not wholly comprehend, as he looked upon them.

Even at a glance, he saw the singular resemblance of the first Sir Roderick

to himself—a likeness otherwise unduplicated in the family, which tended

to an almost antinomian type. There were the same falcon-like features,

the same pallor of brow and cheek, the same semi-morbid luster of eyes,

the same bloodless lips that seemed to be carven from a marble that had

also been chiselled for the long hollow eyelids. The majority of the Hagdons

were broad and sanguine and ruddy; but in these two, a darker strain had

repeated itself across the centuries. The main difference was in the expression,

for the look of the first Sir Roderick was that of a man who has given

himself with a passionate devotion to all things evil and corrupt; who

has gone down to damnation through some inevitable fatality of his own

being.

Sir Roderick gazed on the picture with a fascination that was partly

horror, and partly the stirring of emotions which he could not have named.

Then he turned to the woman, and a wild agitation overmastered him before

the sullen-smiling mouth and the malign oval of the lovely cheeks. She,

too, was evil, and her beauty was that of Lilith. She was like some crimson-lipped

and honey-scented flower that grows on the brink of hell; but Sir Roderick

knew, with the terror and fearful rapture of one who longs to fling himself

from a precipice, that here was the one woman he might have loved, if haply

he had known her. Then, in a moment of reeling and whirling confusion,

it seemed to him that he known and loved her, though he could not remember

when or where.

The feeling of eery confusion passed; and Sir Roderick began to examine

the brass-bound volumes. They were written in a barbarous decadent Latin,

and dealt mainly with methods and formulas for the evocation of such demons

as Acheront, Amaimon, Asmodi and Ashtoreth, together with innumerable others.

Sir Roderick shuddered at the curious drawings with which they were illuminated;

but they did not detain him long. With a thrill of actual trepidation,

like one who is about to enter some awful and unhallowed place, he took

up the manuscript of yellowing parchment.

It was late afternoon when he began to read; and rays of dusty amber

were slanting through the low panes of the library windows. As he read

on, he gave no heed to the sinking of the light; and the last words were

plain as runes of fire when he finished his perusal in the dusk. He closed

his eyes, and could still see them:

"And Sir Roderick Hagdonne was now deemed a moste infamous warlocke,

and hys Ladye Elinore a nefandous witche. . . . And both were burned at

the stake on Hagdonne Common for their crimes against God and man. And

their sorcerous deedes and practices were thought so foule a blotte on

ye knighthoode of England, that no man speaks thereof, and no grandam tells

the tale to the children at her knee. So, by God Hys mercy, the memorie

of thys foulnesse shall haply be forgotten; for sorely itte were an ill

thing that such should be recalled."

Then, at the very bottom of the page, there was a brief, mysterious

footnote in a finer hand than the rest:

"There be those amid the thronge who deemed that they saw Sir Rodericke

vanish when the flames leaped high; and thys, if true, is the moste damnable

proof of hys compact and hys commerce with the Evil One. "

Sir Roderick sat for a long while in the thickening twilight. He

was unstrung, he was abnormally shaken and distraught by the biographical

record he had just read—a record that had been written by some unknown

hand in a bygone century. It was not pleasant for any man to find a tale

so dreadful amid the archives of his family history. But the fact that

the narrative concerned the first Sir Roderick and his Lady Elinor was

hardly enough to account for all the spiritual turmoil and horror into

which he was plunged. Somehow, in a way that was past analysis, that was

more intimate than his regard for the remote blot on the Hagdon name, he

felt that the thing concerned himself also. A terrible nervous perturbation

possessed him, his very sense of identity was troubled, he was adrift in

a sea of abominable confusion, of disoriented thoughts and capsizing memories.

In this peculiar state of mind, by an automatic impulse, he lit the floor-lamp

beside his chair and began to re-read the manuscript.

Almost in the casual manner of a modern tale, the story opened with

an account of Sir Roderick's first meeting, at the age of twenty-three,

with Elinor D'Avenant, who was afterward to become his wife.

This time, as he read, a peculiar hallucination seized the new baronet

It seemed to him that the words of the old writing had begun to waver and

change beneath his scrutiny; that, under the black lines of script on yellowing

parchment, the picture of an actual place was forming. The page expanded,

the letters grew dim and gigantic; they seemed to fade out in midair, and

the picture behind them was no longer a picture, but the very scene of

the narrative. As if the wording were a necromantic spell, the room about

him had vanished like the chamber of a dream; and he stood in the open

sunlight of a windy moor. Bees were humming around him, and the scent of

heather was in his nostrils. His consciousness was indescribably dual;

somewhere, he knew, one part of his brain was still reading the ancient

record; but the rest of his personality had become identified with that

of the first Sir Roderick Hagdon. Inevitably, with no surprize or astonishment,

he found himself living in a bygone age, with the perceptions and memories

of an ancestor who was long dead.

"Now Sir Roderick Hagdonne, being in the flower of hys youth, became

instantlie enamoured of the beauteous Elinore D'Avenant, whenas he mette

her of an Aprile morn on Hagdonne heathe."

Sir Roderick saw that he was not alone on the moor. A woman was coming

toward him along the narrow path amid the heather. Though clad in the conventional

gown and bodice of the period, she was somehow foreign and exotic to that

familiar English landscape. She was the woman of the portrait which, in

a later life, as another Sir Roderick, he had found in a sealed room of

the manor-house. (But this, like much else, he had now forgotten.) Walking

with a languid grace amid the homely blossoms of the heath, her beauty

was like that of some opulent and sinister lily from Saracenic lands. He

thought that he had never seen any one half so strange and lovely.

He stood to one side in the stiff growth, and bowed before her with

a knightly courtesy as she passed. She nodded slightly in acknowledgment,

and gave him an unfathomable smile and an oblique flash of her dark eyes.

From that time, Sir Roderick was her slave and her devotee: he stared after

her as she disappeared on the curving slope, and felt the mounting of an

irresistible flame in his heart, and the stirring of hot desires and curiosities.

He seemed to inhale the spice of a languorous alien perfume with every

breath of the homeland air, as he walked onward, musing with ingenuous

rapture on the dark, enigmatic beauty of the face he had seen.

Now, in that queer necromantic dream, Sir Roderick seemed to live,

or re-live, the events of an entire lustrum. Somewhere, in another existence,

another self was conning briefly the paragraphs which detailed these events;

but of this he was conscious only at long intervals, and then vaguely.

So complete was his immersion in the progress of the tale (as if he had

drunk of that Lethe which alone makes it possible to live again) that he

was untroubled by any prevision of a future known to the Sir Roderick who

sat re-reading an old manuscript. Even as it was written, he returned from

the moor to Hagdon Hall with the vision of a fair stranger in his heart;

he made inquiries concerning her, and learned that she was the daughter

of Sir John D'Avenant, who had but recently received his knighthood for

diplomatic services, and had now taken up his abode on the state near Hagdon

that went with his title. Sir Roderick was now doubly impelled to call

on his new neighbors; and his first visit was soon repeated. He became

an open suitor for the hand of Elinor D'Avenant; and, after a wooing of

several months, he married her

The passionate love with which she had inspired him was only deepened

by their life together. Always her allurement was that of things half understood,

of momentous revelations eternally half withheld. She seemed to love him

truly in return; but ever her heart and soul were strange to him, ever

they were mysterious and exotic, even as the first sight of her face had

been. For this, mayhap, he loved her all the more. They were happy together;

and she bore him one child, a son whom they named Ralph.

Now, in that other life, the Sir Roderick who was reading in the

old library came to these words:

"No man knew how it happed; but anon there were dreade whispers and

foule rumours regarding the Ladye Elinore; and people said that she was

a witch. And in their time these rumours reached the eare of Sir Roderick."

A horror crept upon the happy dream—a horror scarce to be comprehended

in this modern age. There were formless evil wings that came to brood above

Hagdon Hall; and the very air was poisoned with malignant murmurs. Day

by day, and night by night, the baronet was tortured with a vile, unholy

suspicion of the woman he loved. He watched her with a fearful anxiety,

with eyes that dreaded to discern a new and more ominous meaning in her

strange beauty. Then, when he could bear it no longer, he taxed her with

the infamous things he had heard, hoping she would deny them and by virtue

of her denial restore fully his former trust and peace of mind.

To his utter consternation, the Lady Elinor laughed in his face,

with a soft, siren-like mirth, and made open avowal that the charges were

true.

"And I trow," she added, "that you love me too well to disown or

betray me; that for my sake, if need be, you will become a veritable wizard,

even as I am a witch; and will share with me the infernal sports of the

Sabbat."'

Sir Roderick pleaded, he cajoled, he commanded, he threatened; but

ever she answered him with voluptuous laughter and Circean smiles; and

ever she told him of those delights and privileges which are procurable

only through damnation, through the perilous aid of demons and succubi.

Till, through his exceeding love for her, even as she had foretold, Sir

Roderick suffered himself to become an initiate in the arts of sorcery;

and sealed his own pact with the powers of evil, that he might in all things

be made forever one with her that he loved so dearly.

It was an age of dark beliefs and of practises that were no less

dark; and witchcraft and sorcery were rampant throughout the land, among

all classes. But in the Lilith-like Elinor there was a spirit of soulless,

depravity beyond that of all others; and beneath the seduction of her love

the hapless Sir Roderick fell to depths wherefrom no man could return,

and made mortgage of his soul and brain and body to Satan. He learned the

varying malefic usages to which a waxen image could be put; he memorized

the formulas that summon frightful things from their abode in the nethermost

night, or compel the dead to do the abominable will of necromancers. And

he was taught the secrets whereof it is unlawful to tell or even hint;

and came to know the maledictions and invultuations which are lethal to

more than the mortal flesh. And Hagdon Hall became the scene of pandemonian

revels, of rites that were both obscene and blasphemous; and the terror

and turpitude of hellish things were effluent therefrom on all the countryside.

And amid her coterie of the damned, amid the witches and sorcerers and

incubi that fawned upon her, the Lady Elinor exulted openly; and Sir Roderick

was her partner in each new enormity or baleful deed. And in this atmosphere

of noisome things, of Satanic crime and sacrilege, the child Ralph was

alone innocent, being too young to be harmed thereby as yet. But anon the

scandal of it all was a horror in men's souls that could be endured no

longer; and the justice of the law, which made a felony of witchcraft,

was called upon by the people of Hagdon.

It was no new thing for members of the nobility to be tried on such

a charge before the secular or ecclesiastical courts. Such cases, in which

the accusations were often doubtful or prompted by mere malice, had sometimes

been fought at length. But this time the guilt of the defendants was so

universally maintained, and the reprobation arouse thereby so profound,

that only the briefest and most perfunctory trial was accorded them. They

were sentenced to be burnt at the stake; the sentence to be carried out

on the following day.

It was a chill, dank morning in autumn when Sir Roderick and Lady

Elinor were borne to the place of execution and were tied to their respective

stakes, with piles of dry fagots at their feet. They were set facing each

other, so that neither might lose any detail of their mutual agony. A crowd

was gathered about them, thronging the entire common —a crowd whose awful

silence was unbroken by any outcry or murmur. So deep was the terror wrought

by this infamous couple, that no one dared to execrate or mock them even

in the hour of their downfall. Sir Roderick's brain was benumbed by the

obloquy and shame and horror of his situation, by a realization of the

ultimate depths to which he had fallen, of the bitter doom that was now

imminent. He looked at his wife, and thought of how she had drawn him down

from evil to evil through his surpassing love for her; and then he thought

of the frightful searing pains that would convulse her soft body; and thinking

of these he forgot his own fate.

Then, in a dim, exiguous manner, he remembered that somewhere in

another century there sat another Sir Roderick who was reading all this

in an old manuscript. If he could only break the necromantic spell of the

tale, and re-identify himself with that other Sir Roderick, he would be

saved from the fiery doom that awaited him, but if he could not deny the

spell, he would surely perish, even as a falling man who reaches bottom

in a dream is said to perish.

He looked again, and met the gaze of the Lady Elinor. She smiled

across her bonds and fagots, with all the old seduction that had been so

fatal to him. In the re-attained duality of his consciousness, it seemed

as if she were aware of his intention and had willed to deter him. The

ache and anguish of a deadly lure was upon him, as he closed his eyes and

tried very hard to picture the old library and the very sheet of parchment

which his other self was now perusing. If he could do this, the whole diabolical

illusion would vanish, the process of visualization and sympathetic identification

which had been carried to an hallucinative degree, would return to that

which is normally experienced by the reader of an absorbing tale.

There was a crackling at his feet, for some one had lit the fagots.

Sir Roderick opened his eyes a little, and saw that the pile at Lady Elinor's

feet had likewise been lit. Threads of smoke were rising from each pile,

with tiny tongues of flame that grew longer momently. He did not lift his

eyes to the level of Lady Elinor's face. Resolutely he closed them again,

and sought to re-summon the written page.

He was aware of a browing warmth underneath his soles; and now, with

an agonizing flash of pain, he felt the licking of the flames about his

ankles. But somehow, by a desperate effort of his will, like one who awakens

voluntarily from a clutching nightmare, he saw before him the written words

he was trying to visualize:

"And both were burned at the stake on Hagdonne Common for their crimes

against God and man."

The words wavered, they receded and drew near on a page that was

still dim and enormous. But the crackling at his feet had ceased; the air

was no longer dank and chill, no longer charged with acrid smoke. There

was a moment of madly whirling vertigo and confusion; and then Sir Roderick's

two selves were re-united, and he found that he was sitting in the library

chair at Hagdon, staring with open eyes at the last sentences of the manuscript

in his hands.

He felt as if he had been through some infernal ordeal that had lasted

many years; and he was still half obsessed by emotions of sorrow and regret

and horror that could belong only to a dead progenitor. But the whole thing

was manifestly a dream, albeit terrible and real to a degree that he had

never before experienced. He must have fallen asleep over the old record.

. . . But why, then, if it were only a dream, did his ankles still pain

him so frightfully, as if they had been seared by fire?

He bent down and examined them: beneath the Twentieth Century hose

in which they were attired, he found the upward-flaring marks of recent

burns!