Among the many gargoyles that frowned or leered from the roof of the new-built

cathedral of Vyones, two were pre-eminent above the rest by virtue of their

fine workmanship and their supreme grotesquery. These two had been wrought

by the stone-carver Blaise Reynard, a native of Vyones, who had lately

returned from a long sojourn in the cities of Provence, and had secured

employment on the cathedral when the three years' task of its construction

and ornamentation was well-nigh completed. In view of the wonderful artistry

shown by Reynard, it was regretted by Ambrosius, the archbishop, that it

had not been possible to commit the execution of all the gargoyles to this

delicate and accomplished workman; but other people, with less liberal

tastes than

Among the many gargoyles that frowned or leered from the roof of the new-built

cathedral of Vyones, two were pre-eminent above the rest by virtue of their

fine workmanship and their supreme grotesquery. These two had been wrought

by the stone-carver Blaise Reynard, a native of Vyones, who had lately

returned from a long sojourn in the cities of Provence, and had secured

employment on the cathedral when the three years' task of its construction

and ornamentation was well-nigh completed. In view of the wonderful artistry

shown by Reynard, it was regretted by Ambrosius, the archbishop, that it

had not been possible to commit the execution of all the gargoyles to this

delicate and accomplished workman; but other people, with less liberal

tastes than

Ambrosius, were heard to express a different opinion.

This opinion, perhaps, was tinged by the personal dislike that had

been generally felt toward Reynard in Vyones even from his boyhood; and

which had been revived with some virulence on his return. Whether rightly

or unjustly, his very physiognomy had always marked him out for public

disfavor: he was inordinately dark, with hair and beard of a preternatural

bluish-black, and slanting, ill-matched eyes that gave him a sinister and

cunning air. His taciturn and saturnine ways were such as a superstitious

people would identify with necromantic knowledge or complicity; and there

were those who covertly accused him of being in league with Satan; though

the accusations were little more than vague, anonymous rumors, even to

the end, through lack of veritable evidence.

However, the people who suspected Reynard of diabolic affiliations

were wont for awhile to instance the two gargoyles as sufficient proof.

No man, they contended, who was so inspired by the Arch-Enemy, could have

carven anything so sheerly evil and malignant, could have embodied so consummately

in mere stone the living lineaments of the most demoniacal of all the deadly

Sins.

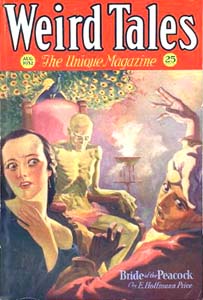

The two gargoyles were perched on opposite corners of a high tower

of the cathedral. One was a snarling, murderous, cat-headed monster, with

retracted lips revealing formidable fangs, and eyes that glared intolerable

hatred from beneath ferine brows. This creature had the claws and wings

of a griffin, and seemed as if it were poised in readiness to swoop down

on the city of Vyones, like a harpy on its prey. Its companion was a horned

satyr, with the vans of some great bat such as might roam the nether caverns,

with sharp, clenching talons, and a look of Satanically brooding lust,

as if it were gloating above the helpless object of its unclean desire.

Both figures were complete, even to the hindquarters, and were not mere

conventional adjuncts of the roof. One would have expected them to start

at any moment from the stone in which they were mortised.

Ambrosius, a lover of art, had been openly delighted with these creations,

because of their high technical merit and their verisimilitude as works

of sculpture. But others, including many humbler dignitaries of the Church,

were more or less scandalized, and said that the workman had informed these

figures with the visible likeness of his own vices, to the glory of Belial

rather than of God, and had thus perpetrated a sort of blasphemy. Of course,

they admitted, a certain amount of grotesquery was requisite in gargoyles;

but in this case the allowable bounds had been egregiously overpassed.

However, with the completion of the cathedral, and in spite of all

this adverse criticism, the high-poised gargoyles of Blaise Reynard, like

all other details of the building, were soon taken for granted through

mere everyday familiarity; and eventually they were almost forgotten. The

scandal of opposition died down, and the stone-carver himself, though the

town-folk continued to eye him askance, was able to secure other work through

the favor of discriminating patrons. He remained in Vyones; and paid his

addresses, albeit without visible success, to a taverner's daughter, one

Nicolette Villom, of whom, it was said, he had long been enamored in his

own surly and reticent fashion.

But Reynard himself had not forgotten the gargoyles. Often, in passing

the superb pile of the cathedral, he would gaze up at them with a secret

satisfaction whose cause he could hardly have assigned or delimited. They

seemed to retain for him a rare and mystical meaning, to signalize an obscure

but pleasurable triumph.

He would have said, if asked for the reason for his satisfaction,

that he was proud of a skilful piece of handiwork. He would not have said,

and perhaps would not even have known, that in one of the gargoyles he

had imprisoned all his festering rancor, all his answering spleen and hatred

toward the people of Vyones, who had always hated him; and had set the

image of this rancor to peer venomously down for ever from a lofty place.

And perhaps he would not even have dreamt that in the second gargoyle he

had somehow expressed his own dour and satyr-like passion for the girl

Nicolette — a passion that had brought him back to the detested city of

his youth after years of wandering; a passion singularly tenacious of one

object, and differing in this regard from the ordinary lusts of a nature

so brutal as Reynard's.

Always to the stone-cutter, even more than to those who had criticized

and abhorred his productions, the gargoyles were alive, they possessed

a vitality and a sentiency of their own. And most of all did they seem

to live when the summer drew to an end and the autumn rains had gathered

upon Vyones. Then, when the full cathedral gutters poured above the streets,

one might have thought that the actual spittle of a foul maelevolence,

the very slaver of an impure lust, had somehow been mingled with the water

that ran in rills from the mouths of the gargoyles.

At that time, in the year of our Lord, 1138, Vyones was the principal

town of the province of Averoigne. On two sides the great, shadow-haunted

forest, a place of equivocal legends, of loups-garous and phantoms, approached

to the very walls and flung its umbrage upon them at early forenoon and

evening. On the other sides there lay cultivated fields, and gentle streams

that meandered among willows or poplars, and roads that ran through an

open plain to the high chateaux of noble lords and to regions beyond Averoigne.

The town itself was prosperous, and had never shared in the ill-fame

of the bordering forest. It had long been sanctified by the presence of

two nunneries and a monastery; and now, with the completion of the long-planned

cathedral, it was thought that Vyones would have henceforward the additional

protection of a more august holiness; that demon and stryge and incubus

would keep their distance from its heaven-favored purlieus with a more

meticulous caution than before.

Of course, as in all mediaeval towns, there had been occasional instances

of alleged sorcery or demoniacal possession; and, once or twice, the perilous

temptations of succubi had made their inroads on the pious virtue of Vyones.

But this was nothing more than might be expected, in a world where the

Devil and his works were always more or less rampant. No one could possibly

have anticipated the reign of infernal horrors that was to make hideous

the latter months of autumn, following the cathedral's erection.

To make the matter even more inexplicable, and more blasphemously

dreadful than it would otherwise have been, the first of these horrors

occurred in the neighborhood of the cathedral itself and almost beneath

its sheltering shadow.

Two men, a respectable clothier named Guillaume Maspier and an equally

reputable cooper, one Gerome Mazzal, were returning to their lodgings in

the late hours of a November eve, after imbibing both the red and white

wines of the countryside in more than one tavern. According to Maspier,

who alone survived to tell the tale, they were passing along a street that

skirted the cathedral square, and could see the bulk of the great building

against the stars, when a flying monster, black as the soot of Abaddon,

had descended upon them from the heavens and assailed Gerome Mazzal, beating

him down with its heavily flapping wings and seizing him with its inch-long

teeth and talons.

Maspier was unable to describe the creature with minuteness, for

he had seen it but dimly and partially in the unlit street; and moreover,

the fate of his companion, who had fallen to the cobblestones with the

black devil snarling and tearing at his throat, had not induced Maspier

to linger in that vicinity. He had betaken himself from the scene with

all the celerity of which he was capable, and had stopped only at the house

of a priest, many streets away, where he had related his adventure between

shudderings and hiccuppings.

Armed with holy water and aspergillus, and accompanied by many of

the towns-people carrying torches, staves and halberds, the priest was

led by Maspier to the place of the horror; and there they had found the

body of Mazzal, with fearfully mangled face, and throat and bosom lined

with bloody lacerations. The demoniac assailant had flown, and it was not

seen or encountered again that night; but those who had beheld its work

returned aghast to their homes, feeling that a creature of nethermost hell

had come to visit the city, and perchance to abide therein.

Consternation was rife on the morrow, when the story became generally

known; and rites of exorcism against the invading demon were performed

by the clergy in all public places and before thresholds. But the sprinkling

of holy water and the mumbling of the stated forms were futile; for the

evil spirit was still abroad, and its malignity was proved once more, on

the night following the ghastly death of Gerome Mazzal.

This time, it claimed two victims, burghers of high probity and some

consequence, on whom it descended in a narrow alley, slaying one of them

instantaneously, and dragging down the other from behind as he sought to

flee. The shrill cries of the helpless men, and the guttural growling of

the demon, were heard by people in the houses along the alley; and some,

who were hardy enough to peer from their windows, had seen the departure

of the infamous assailant, blotting out the autumn stars with the sable

and misshapen foulness of its wings, and hovering in execrable menace above

the house-tops.

After this, few people would venture abroad at night, unless in case

of dire and exigent need; and those who did venture went in armed companies

and were all furnished with flambeaux, thinking thus to frighten away the

demon, which they adjudged a creature of darkness that would abhor the

light and shrink therefrom, through the nature of its kind. But the boldness

of this fiend was beyond measure; for it proceeded to attack more than

one company of worthy citizens, disregarding the flaring torches that were

thrust in its face, or putting them out with th stenchful wind of its wide

vans.

Evidently it was a spirit of homicidal hate, for all the people on

whom it seized were grievously mangled or torn to numberless shreds by

its teeth and talons. Those who saw it, and survived, were wont to describe

it variously and with much ambiguity; but all agreed in attributing to

it the head of a ferocious animal and the wings of a monstrous bird. Some,

the most learned in demonology, were fain to identify it with Modo, the

spirit of murder; and others took it for one of the great lieutenants of

Satan, perhaps Amaimon or Alastor, gone mad with exasperation at the impregnable

supremacy of Christ in the holy city of Vyones.

The terror that soon prevailed, beneath the widening scope of these

Satanical incursions and depredations, was beyond all belief — a clotted,

seething, devil-ridden gloom of superstitious obsession, not to be hinted

at in modern language. Even by daylight, the Gothic wings of nightmare

seemed to brood in underparting oppression above the city; and fear was

everywhere, like the foul contagion of some epidemic plague. The inhabitants

went their way in prayer and trembling; and the archbishop himself, as

well as the subordinate clergy, confessed an inability to cope with the

ever-growing horror. An emissary was sent to Rome, to procure water that

had been specially sanctified by the Pope. This alone it was thought, would

be efficacious enough to drive away the dreadful visitant.

In the meantime, the horror waxed, and mounted to its culmination.

One eve, toward the middle of November, the abbot of the local monastery

of Cordeliers, who had gone forth to administer extreme unction to a dying

friend, was seized by the black devil just as he approached the threshold

of his destination, and was slain in the same atrocious manner as the other

victims.

To this doubly infamous deed, a scarce-believable blasphemy was soon

added. On the very next night, while the torn body of the abbot lay on

a rich catafalque in the cathedral, and masses were being said and tapers

burnt, the demon invaded the high nave through the open door, extinguished

all the candles with one flap of its sooty wings, and dragged down no less

than three of the officiating priests to an unholy death in the darkness.

Every one now felt that a truly formidable assault was being made

by the powers of Evil on the Christian probity of Vyones. In the condition

of abject terror, of extreme disorder and demoralization that followed

upon this new atrocity, there was a deplorable outbreak of human crime,

of murder and rapine and thievery, together with covert manifestations

of Satanism, and celebrations of the Black Mass attended by many neophytes.

Then, in the midst of all this pandemoniacal fear and confusion,

it was rumored that a second devil had been seen in Vyones; that the murderous

fiend was accompanied by a spirit of equal deformity and darkness, whose

intentions were those of lechery, and which molested none but women. This

creature had frightened several dames and demoiselles and maid-servants

into a veritable hysteria by peering through their bedroom windows; and

had sidled lasciviously, with uncouth mows and grimaces, and grotesque

flappings of its bat-shaped wings, toward others who had occasion to fare

from house to house across the nocturnal streets.

However, strange to say, there were no authentic instances in which

the chastity of any woman had suffered actual harm from this noisome incubus.

Many were approached by it, and were terrified immoderately by the hideousness

and lustfulness of its demeanor; but no one was ever touched. Even in that

time of horror, both spiritual and corporeal, there were those who made

a ribald jest of this singular abstention on the part of the demon, and

said it was seeking throughout Vyones for some one whom it had not yet

found.

The lodgings of Blaise Reynard were separated only by the length

of a dark and crooked alley from the tavern kept by Jean Villom, the father

of Nicolette. In this tavern, Reynard had been wont to spend his evenings;

though his suit was frowned upon by Jean Villom, and had received but scant

encouragement from the girl herself. However, because of his well-filled

purse and his almost illimitable capacity for wine, Reynard was tolerated.

He came early each night, with the falling of darkness, and would sit in

silence hour after hour, staring with hot and sullen eyes at Nicolette,

and gulping joylessly the potent vintages of Averoigne. Apart from their

desire to retain his custom, the people of the tavern were a little afraid

of him, on account of his dubious an semi-sorcerous reputation, and also

because of his surly temper. They did not wish to antagonize him more than

was necessary.

Like everyone else in Vyones, Reynard had felt the suffocating burden

of superstitious terror during those nights when the fiendish marauder

was hovering above the town and might descend on the luckless wayfarer

at any moment, in any locality. Nothing less urgent and imperative than

the obsession of his half-bestial longing for Nicolette could have induced

him to traverse after dark the length of the winding alley to the tavern

door.

The autumn nights had been moonless. Now, on the evening that followed

the desecration of the cathedral itself by the murderous devil, a new-born

crescent was lowering its fragile, sanguine-colored horn beyond the house-tops

as Reynard went forth from his lodgings at the accustomed hour. He lost

sight of its comforting beam in the high-walled and narrow alley, and shivered

with dread as he hastened onward through shadows that were dissipated only

by the rare and timid ray from some lofty window. It seemed to him, at

each turn and angle, that the gloom was curded by the unclean umbrage of

Satanic wings, and might reveal in another instant the gleaming of abhorrent

eyes ignited by the everlasting coals of the Pit. When he came forth at

the alley's end, he saw with a start of fresh panic that the crescent moon

was blotted out by a cloud that had the semblance of uncouthly arched and

pointed vans.

He reached the tavern with a sense of supreme relief, for he had

begun to feel a distinct intuition that someone or something was following

him, unheard and invisible — a presence that seemed to load the dusk with

prodigious menace. He entered, and closed the door behind him very quickly,

as if he were shutting it in the face of a dread pursuer.

There were few people in the tavern that evening. The girl Nicolette

was serving wine to a mercer's assistant, one Raoul Coupain, a personable

youth and a newcomer in the neighborhood, and she was laughing with what

Reynard considered unseemly gayety at the broad jests and amorous sallies

of this Raoul. Jean Villom was discussing in a low voice the latest enormities

and was drinking fully as much liquor as his customers.

Glowering with jealousy at the presence of Raoul Coupain, whom he

suspected of being a favored rival, Reynard seated himself in silence and

stared malignly at the flirtatious couple. No one seemed to have noticed

his entrance; for Villom went on talking to his cronies without pause or

interruption, and Nicolette and her companion were equally oblivious. To

his jealous rage, Reynard soon added the resentment of one who feels that

he is being deliberately ignored. He began to pound on the table with his

heavy fists, to attract attention.

Villom, who had been sitting all the while his back turned, now called

out to Nicolette without even troubling to face around on his stool, telling

her to serve Reynard. Giving a backward smile at Coupain, she came slowly

and with open reluctance to the stone-carver's table.

She was small and buxom, with reddish-gold hair that curled luxuriantly

above the short, delicious oval of her face; and she was gowned in a tight-fitting

dress of apple-green that revealed the firm, seductive outlines of her

hips and bosom. Her air was disdainful and a little cold, for she did not

like Reynard and had taken small pains at any time to conceal her aversion.

But to Reynard she was lovelier and more desirable than ever, and he felt

a savage impulse to seize her in his arms and carry her bodily away from

the tavern before the eyes of Raoul Coupain and her father.

"Bring me a pitcher of La Frenaie," he ordered gruffly, in a voice

that betrayed his mingled resentment and desire.

Tossing her head lightly and scornfully, with more glances at Coupain,

the girl obeyed. She placed the fierey, blood-dark wine before Reynard

without speaking, and then went back to resume her bantering with the mercer's

assistant.

Reynard began to drink, and the potent vintage merely served to inflame

his smoldering enmity and passion. His eyes became venomous, his curling

lips malignant as those of the gargoyles he had carved on the new cathedral.

A baleful, primordial anger, like the rage of some morose and thwarted

faun, burned within him with its slow red fire; but he strove to repress

it, and sat silent and motionless, except for the frequent filling and

emptying of his wine-cup.

Raoul Coupain had also consumed a liberal quantity of wine. As a

result, he soon became bolder in his love-making, and strove to kiss the

hand of Nicolette, who had now seated herself on the bench beside him.

The hand was playfully with-held; and then, after its owner had cuffed

Raoul very lightly and briskly, was granted to the claimant in a fashion

that struck Reynard as being no less than wanton.

Snarling inarticulately, with a mad impulse to rush forward and slay

the successful rival with his bare hands, he started to his feet and stepped

toward the playful pair. His movement was noted by one of the men in the

far corner, who spoke warningly to Villom. The tavern-keeper arose, lurching

a little from his potations, and came warily across the room with his eyes

on Reynard, ready to interfere in case of violence.

Reynard paused with momentary irresolution, and then went on, half

insane with a mounting hatred for them all. He longed to kill Villom and

Coupain, to kill the hateful cronies who sat staring from the corner, and

then, above their throttled corpses, to ravage with fierce kisses and vehement

caresses the shrinking lips and body of Nicolette.

Seeing the approach of the stone-carver, and knowing his evil temper

and dark jealousy, Coupain also rose to his feet and plucked stealthily

beneath his cloak at the hilt of a little dagger which he carried. In the

meanwhile, Jean Villom had interposed his burly bulk between the rivals.

For the sake of the tavern's good repute, he wished to prevent the possible

brawl.

"Back to your table, stone-cutter," he roared belligerently at Reynard.

Being unarmed, and seeing himself outnumbered, Reynard paused again,

though his anger still simmered within him like the contents of a sorcerer's

cauldron. With ruddy points of murderous flame in his hollow, slitted eyes,

he glared at the three people before him, and saw beyond them, with instictive

rather than conscious awareness, the leaded panes of the tavern window,

in whose glass the room was dimly reflected with its glowing tapers, its

glimmering tableware, the heads of Coupain and Villom and the girl Nicolette,

and his own shadowy face among them.

Strangely, and, it would seem, inconsequntly, he remembered at that

moment the dark, ambiguous cloud he had seen across the moon, and the insistent

feeling of obscure pursuit while he had traversed the alley.

Then, as he still gazed irresolutely at the group before him, and

its vague reflection in the glass beyond, there came a thunderous crash,

and the panes of the window with their pictured scene were shattered inward

in a score of fragments. Ere the litter of falling glass had reached the

tavern floor, a swart and monstrous form flew into the room, with a beating

of heavy vans that caused the tapers to flare troublously, and the shadows

to dance like a sabbat of misshapen devils. The thing hovered for a moment,

and seemed to tower in a great darkness higher than the ceiling above the

heads of Reynard and the others as they turned toward it. They saw the

malignant burning of its eyes, like coals in the depth of Tartarean pits,

and the curling of its hateful lips on the bared teeth that were longer

and sharper than serpent-fangs.

Behind it now, another shadowy flying monster came in through the

broken window with a loud flapping of its ribbed and pointed wings. There

was something lascivious in the very motion of its flight, even as homicidal

hatred and malignity were manifest in the flight of the other. Its satyr-like

face was twisted in a horrible, never-changing leer, and its lustful eyes

were fixed on Nicolette as it hung in air beside the first intruder.

Reynard, as well as the other men, was petrified by a feeling of

astonishment and consternation so extreme as almost to preclude terror.

Voiceless and motionless, they beheld the demoniac intrusion; and the consternation

of Reynard, in particular, was mingled with an element of unspeakable surprise,

together with a dreadful recognizance. But the girl Nicolette, with a mad

scream of horror, turned and started to flee across the room.

As if her cry had been the one provocation needed, the two demons

swooped upon their victims. One, with a ferocious slash of its outstretched

claws, tore open the throat of Jean Villom, who fell with a gurgling, blood-choked

groan; and then, in the same fashion, it assailed Raoul Coupain. The other,

in the meanwhile, had pursued and overtaken the fleeing girl, and had seized

her

in its bestial forearms, with the ribbed wings enfolding her like

a hellish drapery.

The room was filled by a moaning whirlwind, by a chaos of wild cries

and tossing, struggling shadows. Reynard heard the guttural snarling of

the murderous monster, muffled by the body of Coupain, whom it was tearing

with its teeth; and he heard the lubricous laughter of the incubus, above

the shrieks of the hysterically frightened girl. Then the grotesquely flaring

tapers went out in a gust of swirling air, and Reynard received a violent

blow in the darkness — the blow of some rushing object, perhaps of a passing

wing, that was hard and heavy as stone. He fell, and became insensible.

Dully and confusedly, with much effort, Reynard struggled back to

consciousness. For a brief interim, he could not remember where he was

nor what had happened. He was troubled by the painful throbbing of his

head, by the humming of agitated voices about him, by the glaring of many

lights and the thronging of many faces when he opened his eyes; and above

all, by the sense of nameless but grievous calamity and uttermost horror

that weighed him down from the first dawning of sentiency.

Memory returned to him, laggard and reluctant; and with it, a full

awareness of his surroundings and situation. He was lying on the tavern

floor, and his own warm, sticky blood was rilling across his face from

the wound on his aching head. The long room was half filled with people

of the neighborhood, bearing torches and knives and halberds, who had entered

and were peering at the corpses of Villom and Coupain, which lay amid pools

of wine-diluted blood and the wreckage of the shattered furniture and tableware.

Nicolette, with her green gown in shreds, and her body crushed by

the embraces of the demon, was moaning feebly while women crowded about

her with ineffectual cries and questions which she could not even hear

or understand. The two cronies of Villom, horribly clawed and mangled,

were dead beside their over-turned table.

Stupefied with horror, and still dizzy from the blow that had laid

him unconscious, Reynard staggered to his feet, and found himself surrounded

at once by inquiring faces and voices. Some of the people were a little

suspicious of him, since he was the sole survivor in the tavern, and bore

an ill repute, but his replies to their questions soon convinced them that

the new crime was wholly the work of the same demons that had plagued Vyones

in so monstrous a fashion for weeks past.

Reynard, however, was unable to tell them all that he had seen, or

to confess the ultimate sources of his fear and stupefaction. The secret

of that which he knew was locked in the seething pit of his tortured and

devil-ridden soul.

Somehow, he left the ravaged inn, he pushed his way through the gathering

crowd with its terror-muted murmurs, and found himself alone on the midnight

streets. Heedless of his own possible peril, and scarcely knowing where

he went, he wandered through Vyones for many hours; and somewhile in his

wanderings, he came to his own workshop. With no assignable reason for

the act, he entered, and re-emerged with a heavy hammer, which he carried

with him during his subsequent peregrinations. Then, driven by his awful

and unremissive torture, he went on till the pale dawn had touched the

spires and the house-tops with a ghostly glimmering.

By a half-conscious compulsion, his steps had led him to the square

before the cathedral. Ignoring the amazed verger, who had just opened the

doors, he entered and sought a stairway that wound tortuously upward to

the tower on which his own gargoyles were ensconced.

In the chill and livid light of sunless morning, he emerged on the

roof; and leaning perilously from the verge, he examined the carven figures.

He felt no surprise, only the hideous confirmation of a fear too ghastly

to be named, when he saw that the teeth and claws of the malign, cat-headed

griffin were stained with darkening blood; and that shreds of apple-green

cloth were hanging from the talons of the lustful, bat-winged satyr.

It seemed to Reynard, in the dim ashen light, that a look of unspeakable

triumph, of intolerable irony, was imprinted on the face of this latter

creature. He stared at it with fearful and agonizing fascination, while

impotent rage, abhorrence, and repentance deeper than that of the damned

arose within him in a smothering flood. He was hardly aware that he had

raised the iron hammer and had struck wildly at the satyr's horned profile,

till he heard the sullen, angry clang of impact, and found that he was

tottering on the edge of the roof to retain his balance.

The furious blow had merely chipped the features of the gargoyle,

and had not wiped away the malignant lust and exultation. Again Reynard

raised the heavy hammer.

It fell on empty air; for, even as he struck, the stone-carver felt

himself lifted and drawn backward by something that sank into his flesh

like many separate knives. He staggered helplessly, his feet slipped, and

then he was lying on the granite verge, with his head and shoulders over

the dark, deserted street.

Half swooning, and sick with pain, he saw above him the other gargoyle,

the claws of whose right foreleg were firmly embedded in his shoulder.

They tore deeper, as if with a dreadful clenching. The monster seemed to

tower like some fabulous beast above its prey; and he felt himself slipping

dizzily across the cathedral gutter, with the gargoyle twisting and turning

as if to resume its normal position over the gulf. Its slow, inexorable

movement seemed to be part of his vertigo. The very tower was tilting and

revolving beneath him in some unnatural nightmare fashion.

Dimly, in a daze of fear and agony, Reynard saw the remorseless tiger-face

bending toward him with its horrid teeth laid bare in an eternal rictus

of diabolic hate. Somehow, he had retained the hammer. With an instinctive

impulse to defend himself, he struck at the gargoyle, whose cruel features

seemed to approach him like something seen in the ultimate madness and

distortion of delirium.

Even as he struck, the vertiginous turning movement continued, and

he felt the talons dragging him outward on empty air. In his cramped, recumbent

position, the blow fell short of the hateful face and came down with a

dull clangor on the foreleg whose curving talons were fixed in his shoulder

like meat-hooks. The clangor ended in a sharp cracking sound; and the leaning

gargoyle vanished from Reynard's vision as he fell. He saw nothing more,

except the dark mass of the cathedral tower, that seemed to soar away from

him and to rush upward unbelievably in the livid, starless heavens to which

the belated sun had not yet risen.

It was the archbishop Ambrosius, on his way to early Mass, who found

the shattered body of Reynard lying face downward in the square. Ambrosius

crossed himself in startled horror at the sight; and the, when he saw the

object that was still clinging to Reynard's shoulder, he repeated the gesture

with a more than pious promptness.

He bent down to examine the thing. With the infallible memory of

a true art-lover, he recognized it at once. Then, through the same clearness

of recollection, he saw that the stone foreleg, whose claws were so deeply

buried in Reynard's flesh, had somehow undergone a most unnatural alteration.

The paw, as he remembered it, should have been slightly bent and relaxed;

but now it was stiffly outthrust and elongated, as if, like the paw of

a living limb, it had reached for something, or had dragged a heavy burden

with its ferine talons.