I

am Basil Elton, keeper of the North Point light that my father and grandfather

kept before me. Far from the shore stands the gray lighthouse, above sunken

slimy

I

am Basil Elton, keeper of the North Point light that my father and grandfather

kept before me. Far from the shore stands the gray lighthouse, above sunken

slimy

rocks that are seen when the

tide is low, but unseen when the tide is high. Past that beacon for a century

have swept the majestic barques of the seven seas. In the

days of my grandfather there

were many; in the days of my father not so many; and now there are so few

that I sometimes feel strangely alone, as though I were the last man on

our planet.

From far shores came those white-sailed

argosies of old; from far Eastern shores where warm suns shine and sweet

odors linger about strange gardens and gay

temples. The old captains of

the sea came often to my grandfather and told him of these things which

in turn he told to my father, and my father told to me in the long autumn

evenings when the wind howled eerily from the East. And I have read more

of these things, and of many things besides, in the books men gave me when

I was young and filled with wonder.

But more wonderful than the lore

of old men and the lore of books is the secret lore of ocean. Blue, green,

gray, white or black; smooth, ruffled, or mountainous;

that ocean is not silent. All

my days have I watched it and listened to it, and I know it well. At first

it told to me only the plain little tales of calm beaches and near ports,

but with the years it grew more friendly and spoke of other things; of

things more strange and more distant in space and time. Sometimes at twilight

the gray vapors of the horizon have parted to grant me glimpses of the

ways beyond; and sometimes at night the deep waters of the sea have grown

clear and phosphorescent, to grant me glimpses of the ways beneath. And

these glimpses have been as often of the ways that were and the ways that

might be, as of the ways

that are; for ocean is more

ancient than the mountains, and freighted with the memories and the dreams

of Time.

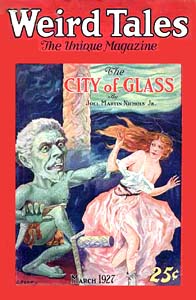

Out of the South it was that

the White Ship used to come when the moon was full and high in the heavens.

Out of the South it would glide very smoothly and silently

over the sea. And whether the

sea was rough or calm, and whether the wind was friendly or adverse, it

would always glide smoothly and silently, its sails distant and

its long strange tiers of oars

moving rhythmically. One night I espied upon the deck a man, bearded and

robed, and he seemed to beckon me to embark for far

unknown shores. Many times afterward

I saw him under the full moon, and never did he beckon me.

Very brightly did the moon shine

on the night I answered the call, and I walked out over the waters to the

White Ship on a bridge of moonbeams. The man who had beckoned now spoke

a welcome to me in a soft language I seemed to know well, and the hours

were filled with soft songs of the oarsmen as we glided away into a mysterious

South, golden with the glow of that full, mellow moon.

And when the day dawned, rosy

and effulgent, I beheld the green shore of far lands, bright and beautiful,

and to me unknown. Up from the sea rose lordly terraces of verdure, tree-studded,

and shewing here and there the gleaming white roofs and colonnades of strange

temples. As we drew nearer the green shore the bearded man told me of that

land, the land of Zar, where dwell all the dreams and thoughts of beauty

that come to men once and then are forgotten. And when I looked upon the

terraces again I saw that what he said was true, for among the sights before

me were many things I had once seen through the mists beyond the horizon

and in the phosphorescent depths of ocean. There too were forms and fantasies

more splendid than any I had ever known; the visions of young poets who

died in want before the world could learn of what they had seen and dreamed.

But we did not set foot upon the sloping meadows of Zar, for it is told

that he who treads them may nevermore return to his native shore.

As the White Ship sailed silently

away from the templed terraces of Zar, we beheld on the distant horizon

ahead the spires of a mighty city; and the bearded man said to me, "This

is Thalarion, the City of a Thousand Wonders, wherein reside all those

mysteries that man has striven in vain to fathom." And I looked again,

at closer range, and saw that the city was greater than any city

I had known or dreamed of before. Into the sky the spires of its temples

reached, so that no man might behold their peaks; and far back beyond the

horizon stretched the grim, gray walls, over which one might spy only a

few roofs, weird and ominous, yet adorned with rich friezes and alluring

sculptures. I yearned mightily to enter this fascinating yet repellent

city, and besought the bearded man to land me at the stone pier by the

huge carven gate Akariel; but he gently denied my wish, saying, "Into Thalarion,

the City of a Thousand Wonders, many have passed but none returned. Therein

walk only daemons and mad things that are no longer men, and the streets

are white with the unburied bones of those who have looked upon the eidolon

Lathi, that reigns over the city." So the White Ship sailed on past the

walls of Thalarion, and followed for many days a southward-flying bird,

whose glossy plumage matched the sky out of which it had appeared.

Then came we to a pleasant coast

gay with blossoms of every hue, where as far inland as we could see basked

lovely groves and radiant arbors beneath a meridian sun. From bowers beyond

our view came bursts of song and snatches of lyric harmony, interspersed

with faint laughter so delicious that I urged the rowers onward in my eagerness

to reach the scene. And the bearded man spoke no word, but watched me as

we approached the lily-lined shore. Suddenly a wind blowing from over the

flowery meadows and leafy woods brought a scent at which I trembled. The

wind grew stronger, and the air was filled with the lethal, charnel odor

of plague-stricken towns and uncovered cemeteries. And as we sailed madly

away from that damnable coast the bearded man spoke at last, saying, "This

is Xura, the Land of Pleasures Unattained."

So once more the White Ship followed

the bird of heaven, over warm blessed seas fanned by caressing, aromatic

breezes. Day after day and night after night did we sail, and when the

moon was full we would listen to soft songs of the oarsmen, sweet as on

that distant night when we sailed away from my far native land. And it

was by moonlight that we anchored at last in the harbor of Sona-Nyl, which

is guarded by twin headlands of crystal that rise from the sea and meet

in a resplendent arch. This is the Land of Fancy, and we walked to the

verdant shore upon a golden bridge of moonbeams.

In the Land of Sona-Nyl there

is neither time nor space, neither suffering nor death; and there I dwelt

for many aeons. Green are the groves and pastures, bright and fragrant

the flowers, blue and musical the streams, clear and cool the fountains,

and stately and gorgeous the temples, castles, and cities of Sona-Nyl.

Of that land there is no bound, for beyond each vista of beauty rises another

more beautiful. Over the countryside and amidst the splendor of cities

can move at will the happy folk, of whom all are gifted with unmarred grace

and unalloyed happiness. For the aeons that I dwelt there I wandered blissfully

through gardens where quaint pagodas peep from pleasing clumps of bushes,

and where the white walks are bordered with delicate blossoms. I climbed

gentle hills from whose summits I could see entrancing panoramas of loveliness,

with steepled towns nestling in verdant valleys, and with the golden domes

of gigantic cities glittering on the infinitely distant horizon. And I

viewed by moonlight the sparkling sea, the crystal headlands, and the placid

harbor wherein lay anchored the White Ship.

It was against the full moon

one night in the immemorial year of Tharp that I saw outlined the beckoning

form of the celestial bird, and felt the first stirrings of unrest.

Then I spoke with the bearded man, and told him of my new yearnings to

depart for remote Cathuria, which no man hath seen, but which all believe

to lie beyond the basalt pillars of the West. It is the Land of Hope, and

in it shine the perfect ideals of all that we know elsewhere; or at least

so men relate. But the bearded man said to me, "Beware of those perilous

seas wherein men say Cathuria lies. In Sona-Nyl there is no pain or death,

but who can tell what lies beyond the basalt pillars of the West?"

Natheless at the next full moon I boarded the White Ship, and with the

reluctant bearded man left the happy harbor for untraveled seas.

And the bird of heaven flew before,

and led us toward the basalt pillars of the West, but this time the oarsmen

sang no soft songs under the full moon. In my mind I would often picture

the unknown Land of Cathuria with its splendid groves and palaces, and

would wonder what new delights there awaited me. "Cathuria," I would say

to myself, "is the abode of gods and the land of unnumbered cities of gold.

Its forests are of aloe and sandalwood, even as the fragrant groves of

Camorin, and among the trees flutter gay birds sweet with song. On the

green and flowery mountains of Cathuria stand temples of pink marble, rich

with carven and painted glories, and having in their courtyards cool fountains

of silver, where purr with ravishing music the scented waters that come

from the grotto-born river Narg. And the cities of Cathuria are cinctured

with golden walls, and their pavements also are of gold. In the gardens

of these cities are strange orchids, and perfumed lakes whose beds are

of coral and amber. At night the streets and the gardens are lit with gay

lanthorns fashioned from the three-colored shell of the tortoise, and here

resound the soft notes of the singer and the lutanist. And the houses of

the cities of Cathuria are all palaces, each built over a fragrant canal

bearing the waters of the sacred Narg. Of marble and porphyry are the houses,

and roofed with glittering gold that reflects the rays of the sun and enhances

the splendor of the cities as blissful gods view them from the distant

peaks. Fairest of all is the palace of the great monarch Dorieb, whom some

say to be a demi-god and others a god. High is the palace of Dorieb, and

many are the turrets of marble upon its walls. In its wide halls many multitudes

assemble, and here hang the trophies of the ages. And the roof is of pure

gold, set upon tall pillars of ruby and azure, and having such carven figures

of gods and heroes that he who looks up to those heights seems to gaze

upon the living Olympus. And the floor of the palace is of glass, under

which flow the cunningly lighted waters of the Narg, gay with gaudy fish

not known beyond the bounds of lovely Cathuria."

Thus would I speak to myself

of Cathuria, but ever would the bearded man warn me to turn back to the

happy shore of Sona-Nyl; for Sona-Nyl is known of men,

while none hath ever beheld

Cathuria.

And on the thirty-first day that

we followed the bird, we beheld the basalt pillars of the West. Shrouded

in mist they were, so that no man might peer beyond them or

see their summits -- which indeed

some say reach even to the heavens. And the bearded man again implored

me to turn back, but I heeded him not; for from the

mists beyond the basalt pillars

I fancied there came the notes of singers and lutanists; sweeter than the

sweetest songs of Sona-Nyl, and sounding mine own praises; the praises

of me, who had voyaged far from the full moon and dwelt in the Land of

Fancy. So to the sound of melody the White Ship sailed into the mist betwixt

the basalt pillars of the West. And when the music ceased and the mist

lifted, we beheld not the Land of Cathuria, but a swift-rushing resistless

sea, over which our helpless barque was borne toward some unknown goal.

Soon to our ears came the distant thunder of falling waters, and to our

eyes appeared on the far horizon ahead the titanic spray of a monstrous

cataract, wherein the oceans of the world drop down to abysmal nothingness.

Then did the bearded man say to me, with tears on his cheek, "We have rejected

the beautiful Land of Sona-Nyl, which we may never behold again. The gods

are greater than men, and they have conquered." And I closed my eyes before

the crash that I knew would come, shutting out the sight of the celestial

bird which flapped its mocking blue wings over the brink of the torrent.

Out of that crash came darkness,

and I heard the shrieking of men and of things which were not men. From

the East tempestuous winds arose, and chilled me as I

crouched on the slab of damp

stone which had risen beneath my feet. Then as I heard another crash I

opened my eyes and beheld myself upon the platform of that

lighthouse whence I had sailed

so many aeons ago. In the darkness below there loomed the vast blurred

outlines of a vessel breaking up on the cruel rocks, and as I glanced out

over the waste I saw that the light had failed for the first time since

my grandfather had assumed its care.

And in the later watches of the

night, when I went within the tower, I saw on the wall a calendar which

still remained as when I had left it at the hour I sailed away.

With the dawn I descended the

tower and looked for wreckage upon the rocks, but what I found was only

this: a strange dead bird whose hue was as of the azure

sky, and a single shattered

spar, of a whiteness greater than that of the wave-tips or of the mountain

snow.

And thereafter the ocean told

me its secrets no more; and though many times since has the moon shone

full and high in the heavens, the White Ship from the South

came never again.