In Which the Telephone Continues Ringing

When he had finished writing he sorted

out some silver, and handed it and the yellow paper to Sacharissa.

"It's dark in here.

Would you mind reading it aloud to me to see if I've made it plain?"

he asked.

"Certainly," said Sacharissa;

and she read:

MRS. DELANCY COURLAND,

Tuxedo.

I'm stuck in an idiotic elevator at 1008-1/2 Fifth Avenue. If

I don't appear by New Year's you'll know why. Be careful that

no reporters get hold of this.

KILLIAN VAN K. VANDERDYNK.

Sacharissa

flushed deeply. "I can't send this," she said.

"Why not?" demanded

the young man, irritably.

"Because, Mr. Vanderdynk,

my father, brother-in-law, married sister, and three younger sisters

are expected at the Courlands'. Imagine what effect such a telegram

would have on them!"

"Then cross out the

street and number," he said; "just say I'm stuck in a strange elevator."

She did so, rang, and

a servant took away the telegram.

"Now," said the heir

apparent to the Prince Regency of Manhattan, "there are two things

still" possible. First, you might ring up police headquarters and

ask for aid; next, request assistance from fire headquarters."

"If I do," she said,

"wouldn't the newspapers get hold of it?"

"You are perfectly

right," he said.

She had now drawn her

chair so close to the gilded grille that, hands resting upon it,

she could look down into the car where sat the scion of the Vanderdynks

on a flimsy Louis XV chair.

"I can't express to

you how sorry I am," she said. "Is there anything I can do to--to

ameliorate your imprisonment?"

He looked at her in

a bewildered way.

"You don't expect me

to remain here until after New Year's, do you?" he inquired.

"I don't see how you

can avoid it. Nobody seems to want to work until after New Year's."

"Stay in a cage--two

days and a night!"

"Perhaps I had better

call up the police."

"No, no! Wait. I'll

tell you what to do. Start that man, Ferdinand, on a tour of the

city. If he hunts hard enough and long enough he'll find some plumber

or locksmith or somebody who'll come."

She rang for Ferdinand;

together they instructed him, and he went away, promising to bring

salvation in some shape.

Which promise made

the young man more cheerful and smoothed out the worried pucker

between Sacharissa's straight brows.

"I suppose," she said,

"that you will never forgive my maid for this--or me either."

He laughed. "After

all," he admitted, "it's rather funny."

"I don't believe you

think it's funny."

"Yes, I do."

"Didn't you want to

go to Tuxedo?"

"I!" He looked up at

the pretty countenance of Sacharissa. "I did want

to--a few minutes ago."

"And now that you can't

your philosophy teaches you that you don't want to?"

They laughed at each

other in friendly fashion.

"Perhaps it's my philosophy,"

he said, "but" I really don't care very much.... I'm not sure that

I care at all.... In fact, now that I think of it, why should I

have wished to go to Tuxedo? It's stupid to want to go to Tuxedo

when New York is so attractive."

"Do you know," she

said reflectively, "that I came to the same conclusion?"

"When?"

"This morning."

"Be-before you--I----"

"Oh, yes," she said

rather hastily, "before you came----"

She broke off, pink

with consternation. What a ridiculous thing to say! What on earth

was twisting her tongue to hint at such an absurdity?

She said, gravely,

with heightened color: "I was standing by the window this morning,

thinking, and it occurred to me that I didn't care to go to Tuxedo....

When did you change your mind?"

"A few minutes a--that

is--well, I never really wanted to go. It's jollier

in town. Don't you think so? Blue sky, snow--er--and all that?"

"Yes," she said, "it

is perfectly delightful in town to-day."

He assented, then looked

discouraged.

"Perhaps you would

like to go out?" he said.

"I? Oh, no.... The

sun on the snow is bad for one's eyes; don't you think so?"

"Very.... I'm terribly

sorry that I'm giving you so much trouble."

"I don't mind--really.

If only I could do something for you."

"You are."

"I?"

"Yes; you are being

exceedingly nice to me. I am afraid you feel under obligations to

remain indoors and----"

"Truly, I don't. I

was not going out."

She leaned nearer and

looked through the bars: "Are you quite sure you feel comfortable?"

"I feel like something

in a zoo!"

She laughed. "That

reminds me," she said, "have you had any luncheon?"

He had not, it appeared,

after a little polite protestation, so she rang for Sparks.

Her own appetite, too,

had returned when the tray was brought; napkin and plate were passed

through the grille to him, and, as they lunched, he in his cage,

she close to the bars, they fell into conversation, exchanging information

concerning mutual acquaintances whom they had expected to meet at

the Delancy Courlands'.

"So you see," she said,

"that if I had not changed my mind about going to Tuxedo this morning

you would not be here now. Nor I.... And we would never have--lunched

together."

"That didn't alter

things," he said, smiling. "If you hadn't been ill you would have

gone to Tuxedo, and I should have seen you there."

"Then, whatever I did

made no difference," she assented, thoughtfully, "for we were bound

to meet, anyway."

He remained standing

close to the grille, which, as she was seated, brought his head

on a level with hers.

"It would seem," he

said laughingly, "as though we were doomed to meet each other, anyway.

It looks like a case of Destiny to me."

She started slightly:

"What did you say?"

"I said that it looks

as though Fate intended us to meet, anyhow. Don't you think so?"

She remained silent.

He added cheerfully:

"I never was afraid of Fate."

"Would you care for

a--a book--or anything?" she asked, aware of a new constraint in

her voice.

"I don't believe I

could see to read in here.... Are you--going?"

"I--ought to." Vexed

at the feeble senselessness of her reply she found herself walking

down the landing, toward nowhere in particular. She turned abruptly

and came back.

"Do you want a book?"

she repeated.

"Oh, I forgot that

you can't see to read. But perhaps you might care to smoke."

"Are you going away?"

"I--don't mind your

smoking."

He lighted a cigarette;

she looked at him irresolutely.

"You mustn't think

of remaining," he said. Whereupon she seated herself.

"I suppose I ought

to try to amuse you--till Ferdinand returns with a plumber," she

said.

He protested: "I couldn't

think of asking so much from you."

"Anyway, it's my duty,"

she insisted. "I ought."

"Why?"

"Because you are under

my roof--a guest."

"Please don't think----"

"But I really don't

mind! If there is anything I can do to make your imprisonment easier----"

"It is easy. I rather

like being here."

"It is very amiable

of you to say so."

"I really mean it."

"How can you really

mean it?"

"I don't know, but

I do." In their earnestness they had come close to the bars; she

stood with both hands resting on the grille, looking in; he in a

similar position, looking out.

He said: "I feel like

an occupant of the Bronx, and it rather astonishes me that you haven't

thrown me in a few peanuts."

She laughed, fetched

her box of chocolates, then began seriously: "If Ferdinand doesn't

find anybody I'm afraid you might be obliged to remain to dinner."

"That prospect," he

said, "is not unpleasant. You know when one becomes accustomed to

one's cage it's rather a bore to be let out."

They sampled the chocolates,

she sitting close to the cage, and as the box would not go through

the bars she was obliged to hand them to him, one by one.

"I wonder," she mused,

"how soon Ferdinand will find a plumber?"

He shrugged his shoulders.

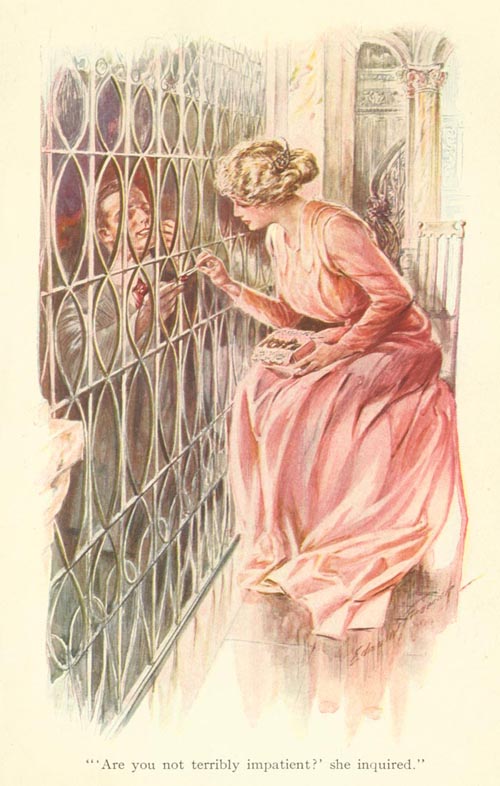

She bent her adorable

head, chose a chocolate and offered it to him.

"Are

you not terribly impatient?" she inquired.

"Not--terribly."

Their glances encountered

and she said hurriedly:

"I am sure you must

be perfectly furious with everybody in this house. I--I think it

is most amiable of you to behave so cheerfully about it."

"As a matter of fact,"

he said, "I'm feeling about as cheerful as I ever felt in my life."

"Cooped up in a cage?"

"Exactly."

"Which may fall at

any--" The idea was a new one to them both. She leaned forward in

sudden consternation. "I never thought of that!" she exclaimed.

"You don't think there's any chance of its falling, do you?"

He looked at the startled,

gray eyes so earnestly fixed on his. The sweet mouth quivered a

little--just a little--or he thought it did.

"No," he replied, with

a slight catch in his voice, "I don't believe it's going to fall."

"Perhaps you had better

not move around very much in it. Be careful, I beg of you. You will,

won't you, Mr. Vanderdynk?"

"Please don't let it

bother you," he said, stepping toward her impulsively.

"Oh, don't, don't move!"

she exclaimed. "You really must keep perfectly still. Won't you

promise me you will keep perfectly still?"

"I'll promise you anything,"

he said a little wildly.

Neither seemed to notice

that he had overdone it.

She drew her chair

as close as it would go to the grille and leaned against it.

"You will

keep up your courage, won't you?" she asked anxiously.

"Certainly. By the

way, how far is it to the b-basement?"

She turned quite white

for an instant, then:

"I think I'd better

go and ring up the police."

"No! A thousand times

no! I couldn't stand that."

"But the car might--drop

before----"

"Better decently dead

than publicly paragraphed.... I haven't the least idea that this

thing is going to drop.... Anyway, it's worth it," he added, rather

vaguely.

"Worth--what?" she

asked, looking into his rather winning, brown eyes.

"Being here," he said,

looking into her engaging gray ones.

After a startling silence

she said calmly: "Will you promise me not to move or shake the car

till I return?"

"You won't be very

long, will you?"

"Not--very," she replied

faintly.

She walked into the

library, halted in the center of the room, hands clasped behind

her. Her heart was beating like a trip hammer.

"I might as well face

it," she said to herself; "he is--by far--the most thoroughly attractive

man I have ever seen.... I--I don't know what's the

matter," she added piteously.... "if it's that machine William made

I can't help it; I don't care any longer; I wish----"

A sharp crack from

the landing sent her out there in a hurry, pale and frightened.

"Something snapped

somewhere," explained the young man with forced carelessness, "some

unimportant splinter gave way and the thing slid down an inch or

two."

"D-do you think----"

"No, I don't. But it's

perfectly fine of you to care."

"C-care? I'm a little

frightened, of course.... Anybody would be.... Oh, I wish you were

out and p-perfectly safe." "If I thought you could ever really care

what became of a man like me----"

Killian Van K. Vanderdynk's

aristocratic senses began gyrating; he grasped the bars, the back

of his hand brushed against hers, and the momentary contact sent

a shock straight through the scion of that celebrated race.

She seated herself

abruptly; a delicate color grew, staining her face.

Neither spoke. A long,

luminous sunbeam fell across the landing, touching the edge of her

hair till it glimmered like bronze afire. The sensitive mouth was

quiet, the eyes, very serious, were lifted from time to time, then

lowered, thoughtfully, to the clasped fingers on her knee.

Could it be possible?

How could it be possible?--with a man she had never before chanced

to meet--with a man she had seen for the first time in her life

only an hour or so ago! Such things didn't happen outside of short

stories. There was neither logic nor common decency in it. Had she

or had she not any ordinary sense remaining?

She raised her eyes

and looked at the heir of the Vanderdynks.

Of course anybody could

see he was unusually attractive--that he had that indefinable something

about him which is seldom, if ever, seen outside of fiction or of

Mr. Gibson's drawings--perhaps it is entirely confined to them--except

in this one very rare case.

Sacharissa's eyes fell.

Another unusual circumstance

was engaging her attention, namely, that his rather remarkable physical

perfection appeared to be matched by a breeding quite as faultless,

and a sublimity of courage in the face of destruction itself, which----

Sacharissa lifted her

gray eyes.

There he stood, suspended

over an abyss, smoking a cigarette, bravely forcing himself to an

attitude of serene insouciance, while the basement yawned for him!

Machine or no machine, how could any girl look upon such miraculous

self-control unmoved? She could not. It was natural

that a woman should be deeply thrilled by such a spectacle--and

William Destyn's machine had nothing to do with it--not a thing!

Neither had psychology, nor demonology, nor anything, with wires

or wireless. She liked him, frankly. Who wouldn't? She feared for

him, desperately. Who wouldn't? She----

"C-r-rack!"

"Oh--what

is it!" she cried, springing to the grille.

"I don't know," he

said, somewhat pale. "The old thing seems--to be sliding."

"Giving way!"

"A--little--I think----"

"Mr. Vanderdynk! I

must call the police----"

"Cr-rackle--crack-k-k!"

went the car, dropping an inch or two.

With a stifled cry

she caught his hands through the bars, as though to hold him by

main strength.

"Are you crazy?" he

said fiercely, thrusting them away. "Be careful! If the thing drops

you'll break your arms!"

"I--I don't care!"

she said breathlessly. "I can't let----"

"Crack!" But the car

stuck again.

"I will

call the police!" she cried.

"The papers may make

fun of you."

"Was it for me

you were afraid? Oh, Mr. Vanderdynk! What do I care for ridicule

compared to--to----"

The car had sunk so

far in the shaft now that she had to kneel and put her head close

to the floor to see him.

"I will only be a minute

at the telephone," she said. "Keep up courage; I am thinking of

you every moment."

"W-will you let me

say one word?" he stammered.

"Oh, what? Be quick,

I beg you."

"It's only goodbye--in

case the thing drops. May I say it?"

"Y-yes--yes! But say

it quickly."

"And if it doesn't

drop after all, you won't be angry at what I'm going to say?"

"N-no. Oh, for Heaven's

sake, hurry!"

"Then--you are the

sweetest woman in the world!... Goodbye--Sacharissa-- dear."

She sprang up, dazed,

and at the same moment a terrific crackling and splintering resounded

from the shaft, and the car sank out of sight.

Faint, she swayed for

a second against the balustrade, then turned and ran downstairs,

ears strained for the sickening crash from below.

There was no crash,

no thud. As she reached the drawing-room landing, to her amazement

a normally-lighted elevator slid slowly down, came to a stop, and

the automatic grilles opened quietly.

As Killian Van K. Vanderdynk

crept forth from the elevator, Sacharissa's nerves gave way; his,

also, seemed to disintegrate; and they stood for some moments mutually

supporting each other, during which interval unaccustomed tears

fell from the gray eyes, and unaccustomed words, breathed brokenly,

reassured her; and, altogether unaccustomed to such things, they

presently found themselves seated in a distant corner of the drawing-room,

still endeavoring to reassure each other with interclasped hands.

They said nothing so

persistently that the wordless minutes throbbed into hours; through

the windows the red west sent a glowing tentacle into the room,

searching the gloom for them.

It fell, warm, across

her upturned throat, in the half light.

For her head lay back

on his shoulder; his head was bent down, lips pressed to the white

hands crushed fragrantly between his own.

A star came out and

looked at them with astonishment; in a little while the sky was

thronged with little stars, all looking through the window at them.

Her maid knocked, backed

out hastily and fled, distracted. Then Ferdinand arrived with a

plumber.

Later the butler came.

They did not notice him until he ventured to cough and announce

dinner.

The interruptions were

very annoying, particularly when she was summoned to the telephone

to speak to her father.

"What is it, dad?"

she asked impatiently.

"Are you all right?"

"Oh, yes," she answered,

carelessly; "we are all right, dad. Goodbye."

"We? Who the devil

is 'We'?"

"Mr. Vanderdynk and

I. We're taking my maid and coming down to Tuxedo this evening together.

I'm in a hurry now."

"What!!!"

"Oh, it's all right,

dad. Here, Killian, please explain things to my father."

Vanderdynk released

her hand and picked up the receiver as though it had been a live

wire.

"Is that you, Mr. Carr?"

he began--stopped short, and stood listening, rigid, bewildered,

turning redder and redder as her father's fluency increased. Then,

without a word, he hooked up the receiver.

"Is it all right?"

she asked calmly. "Was dad--vivacious?"

The young man said:

"I'd rather go back into that elevator than go to Tuxedo.... But--I'm

going."

"So am I," said Bushwyck

Carr's daughter, dropping both hands on her lover's shoulders....

"Was he really very--vivid?"

"Very."

The telephone again

rang furiously.

He bent his head; she

lifted her face and he kissed her.

After a while the racket

of the telephone annoyed them, and they slowly moved away out of

hearing.